Full-endoscopic Foraminotomy in Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: A “Module-based” Approach for Surgical Planning and Execution

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis (DSL) is a common spinal pathology characterized by the anterior slippage of one vertebral body on another. DSL is caused mainly by degeneration of the intervertebral disc in the first place, with subsequent degeneration of the facet joints that end causing the slippage. As the disease evolves, stability is restored as a result of advanced degeneration and disc collapse. But while this natural evolution takes place, DSL may produce radicular symptoms by different mechanisms. To present a “module-based” approach for the surgical planning and execution of full-endoscopic foraminotomy in DSL, combined with case examples of the most common surgical scenarios.

Methods

We propose a “module-based surgery” using the standard endoscopic foraminotomy technique as a baseline. According to the patient’s clinical and imaging characteristics, several “modules” can be added. The resulting endoscopic surgery is a summation of the basic endoscopic foraminotomy plus all the additional required modules.

Results

Surgical modules description and case examples are provided.

Conclusion

Transforaminal lumbar endoscopic foraminotomy represents a minimally invasive technique to treat foraminal and combined foraminal-lateral recess stenosis. DSL and its multiple scenarios represent a challenge to the endoscopic surgeon. Module-based approach can help systematize and execute these demanding endoscopic procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar spondylolisthesis is a common spinal pathology characterized by the anterior slippage of one vertebral body on another. First described in 1931 [1], this pathology can be classified according to broad etiologies [2], being degenerative spondylolisthesis (DSL) the most frequent variety encountered in clinical practice [3]. DSL is caused mainly by degeneration of the intervertebral disc in the first place, with subsequent degeneration of the facet joints that end causing the slippage [4]. As the disease evolves, stability is restored as a result of advanced degeneration and disc collapse. But while this natural evolution takes place, DSL may produce three different types of pain patterns by different mechanisms [5]:

1. Low back pain and referred pain in the back of the thigh, mostly caused by the affected intervertebral disc and facet joints that suffer the stress of the slippage and instability.

2. Radicular pain or motor deficit, caused by narrowing of the foramen and/or lateral recess compressing the exiting or the traversing nerve root, as the case may be.

3. Neurogenic claudication, produced by combined central stenosis secondary to slippage as well as hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and facet joints.

These conditions can present isolated or more commonly combined with other degenerative changes such as disc herniations, etc. configuring different scenarios.

Percutaneous or full-endoscopic procedures have shown good outcomes and decompression effectiveness in patients with lumbar central, lateral recess, and foraminal stenosis [6-9]. Due to the minimally invasive nature of the procedure, transforaminal endoscopic approaches minimize the surgical footprint sparing the stabilizing structures such as ligaments, muscles, and facet joints. This makes endoscopic decompression especially attractive in the setting of DSL. It can become a method to ease the radicular and stenotic symptoms while allowing the DSL to continue its natural path to re-stabilization. Taking into consideration that, as with many minimally invasive procedures, the effectiveness of endoscopic decompression relies on a thorough analysis of the pathology and surgical planning, DSL and its multiple scenarios represent a challenge to the endoscopic surgeon.

We present a “module-based” approach for the surgical planning and execution of full-endoscopic foraminotomy in DSL.

MODULE-BASED APPROACH

Foraminal stenosis in DSL represents a challenge to the endoscopic surgeon, mainly because of its multiple anatomical and clinical variations that results in changes in the standard endoscopic foraminotomy surgical strategy and technique.

To address and systematize these variations, we propose a “module-based surgery” using the standard endoscopic foraminotomy technique as a baseline. According to the patient’s clinical and imaging characteristics, several “modules” can be added. The resulting endoscopic surgery is a summatory of the basic endoscopic foraminotomy plus all the additional required modules.

The inclusion criteria to apply this module-based approach are the following:

- Stable DSL, defined as no radiological instability on dynamic lateral lumbar X-Rays.

- Symptomatic radiculopathy with concordant foraminal stenosis demonstrated on imaging studies.

The exclusion criteria for this approach are:

- Radiological instability on dynamic lateral lumbar X-Rays.

- Significant lumbar pain (lumbar VAS> radicular VAS).

- Central stenosis causing neurogenic claudication.

- Non-degenerative Spondylolisthesis.

Likewise, non-surgical aspects of the patient that can affect the decision-making process and can override the inclusion/exclusion criteria: Patient/family preferences and expectations, possibility of revision surgery, comorbidities (as measured in the Charlson Comorbidity Index).

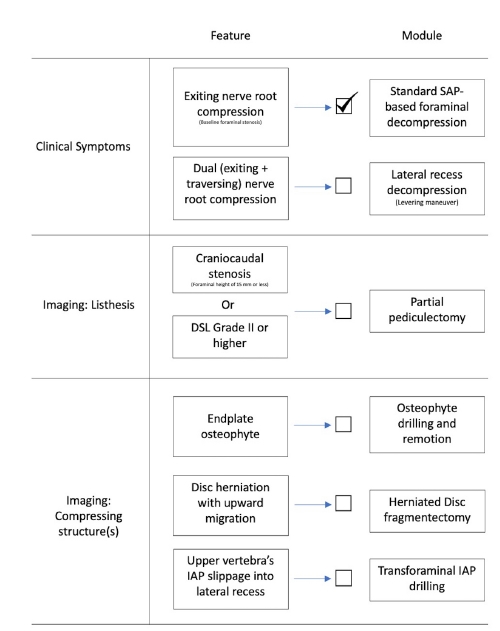

The proposed modules are detailed in Figure 1 [10].

1. Endoscopic Modules: Technical Description

Each endoscopic module can be considered as an independent technical unit. Different modules can be combined according to the patient’s characteristics. The modules are assembled and executed according to a logical rule: first from medial to lateral, and then from caudal to cranial.

2. Standard SAP-based Foraminal Decompression

The transforaminal resection of SAP tip serves as baseline for endoscopic foraminoplasty in the setting of DSL. As a consequence it is considered as the first and indispensable surgical module.

Endoscopic transforaminal SAP resection follows the technique described by Ahn et al. [11]: Puncture site is calculated using preoperative MRI. Needle is advanced until the tip contacts the transition between pedicle and SAP. An 8 mm skin incision is made, and guidewire, blunt dilator and beveled working sheath are placed sequentially. The opening of the beveled working sheath must be “floating free” into the foramen, in gentle contact with the SAP surface. The endoscope is placed through the working sheath and then the resection of the tip of the SAP is carried out under endoscopic visualization using an endoscopic high speed drill. Redundant ligamentum flavum must be removed as well to complete the decompression.

3. Transforaminal Lateral Recess Decompression: Levering Maneuver

Lateral recess decompression can be accomplished both through interlaminar access or transforaminal access [6]. The latter requires a “levering maneuver” that consists in tilting the tip of the endoscope anterior and medial to advance through the previously enlarged foramen into the limits of the lateral recess. An extended resection of the SAP is carried out, and the loosened ligamentum flavum is removed. The resection ends when the traversing nerve root is freed from the axilla of the exiting nerve root (cranial limit) to the inferior pedicle (caudal limit).

4. Partial Pediculectomy

Craniocaudal dimension of the lumbar vertebral foramen can be enlarged by removing the upper portion of the inferior vertebra’s pedicle. The starting point to carry out this partial pediculectomy [6] becomes visible after resecting the base of the SAP: From the lateral and superior margin of the pedicle, the drilling with a diamond burr follows a medial and caudal direction until the upper third of the pedicle is resected (caudal limit), and the ligamentum flavum is exposed (medial limit).

5. Osteophyte Resection

Osteophytes arising from superior or inferior vertebrae’s endplate can be responsible for ventral foraminal stenosis and contribute to exiting nerve root compression. To safely remove these formations, it is preferable to rotate the working sheath until the bevel is covering and protecting the exiting nerve root. Then, proceed to “cavitate” the osteophyte with a diamond burr, keeping intact the bone layer that is in contact with the nerve root. Finally, with a blunt dissector, gently fracture the remaining thin layer of osteophyte away from the nerve root, as described by Lee et al. [12].

6. Disc Fragmentectomy

Another structure that can cause ventral foraminal stenosis and therefore exiting nerve root compression is a herniated intervertebral disc. The disc fragment can be removed according to the outside-in technique described by Schubert and Hoogland [13], simplified by the previous foraminotomy. However, when dealing with a voluminous disc herniation, an early access to the disc nucleus and a subsequent debulking can ease the resection of the herniated fragment.

7. Transforaminal Inferior Articular Process (IAP) Drilling

In DSL with a Meyerding grade II or higher, the vertebral slippage can cause changes in the pattern of lateral recess compression. Instead of the usual SAP related stenosis observed in non DSL patients, the structure often occupying the lateral recess and therefore compressing the traversing nerve root is the slipped tip of the superior vertebra’s IAP. This demands to take the foraminal decompression a step further and include the IAP tip in the drilling plan. According to this, after removing the SAP the endoscope must be advanced medially. Instead of the ligamentum flavum attached to the medial border of the SAP, the IAP will present as a medially situated bony structure that needs to be removed to ensure the complete decompression of the lateral recess. To avoid facet joint injury and instability, IAP resection must be stopped as soon as traversing nerve root is freed.

SURGICAL SCENARIOS

1. Lumbar Mono-radiculopathy Caused by Pure Foraminal Stenosis without Cranio-caudal Compression

1) Case Presentation

A 66 year old female patient with right L4 sciatica pain (VAS 9/10) for the past four months, with no response to medication or physical therapy. Mild lumbar pain (VAS 2/10).

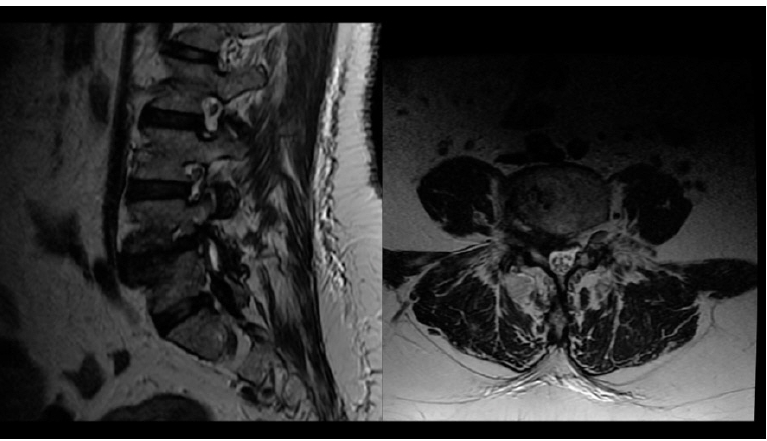

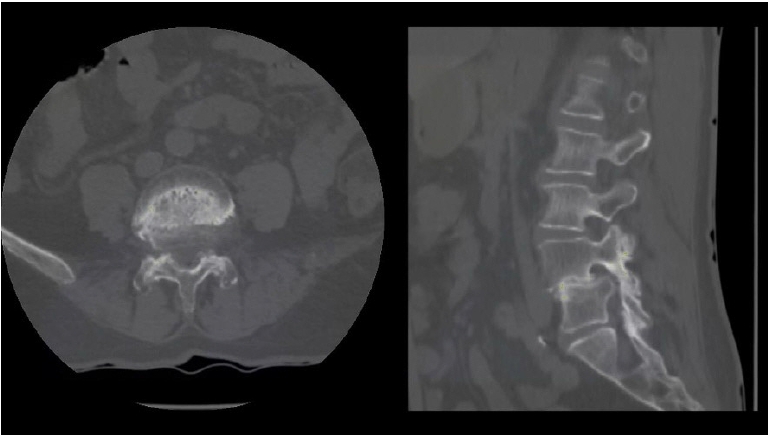

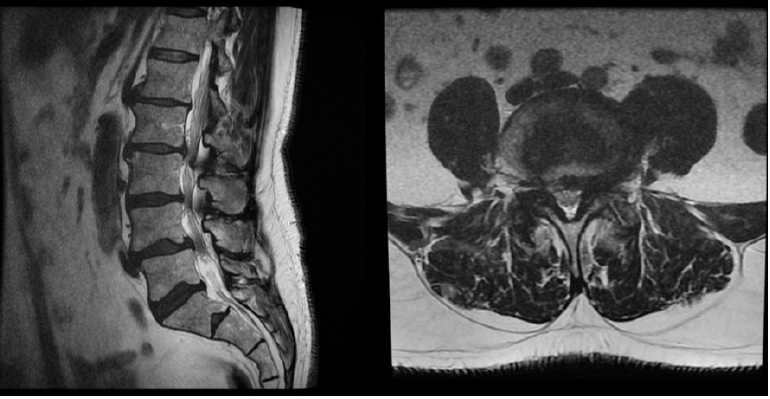

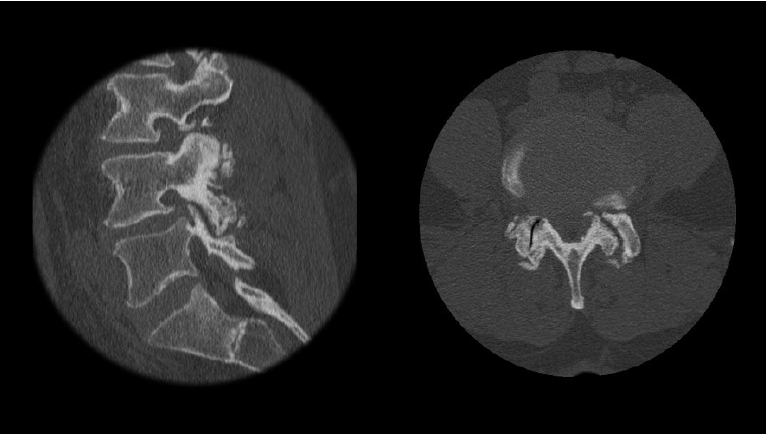

MRI showed Grade II DSL with right L4-L5 foraminal stenosis (Figure 2). CT confirmed that compressing structures were L4-L5 disc herniation and L5 SAP (Figure 3).

2) Modules Assemble

According to the clinical and radiological analysis, the surgery was planned with the following modules: (1) Standard SAP-based foraminotomy; (2) Herniated disc fragmentectomy.

3) Surgical Technique

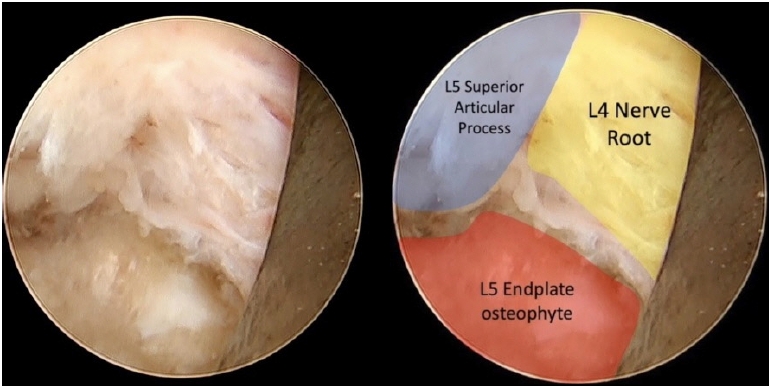

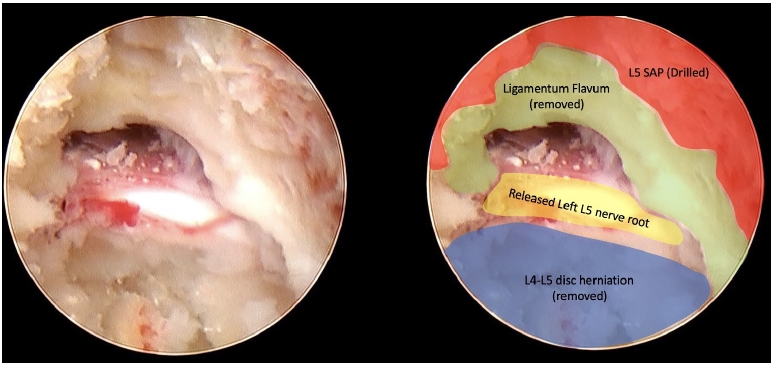

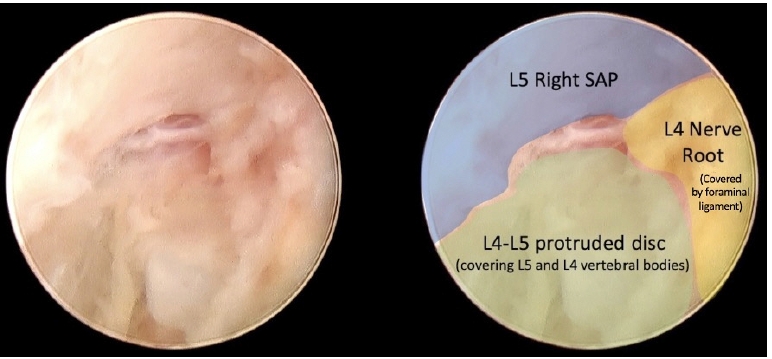

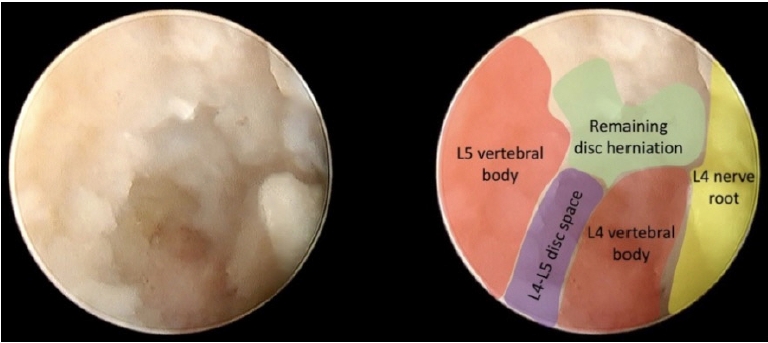

An L4-L5 right posterolateral endoscopic access was performed, 8 cm lateral to midline. The working sheath initially landed on L5 SAP (Figure 4).

Initial view showing L5 right SAP, L4-L5 protruded disc, and foraminal ligament covering L4 nerve root.

After drilling L5 SAP, a safe disc remotion was carried out due to the enlarged dimensions of the foramen.

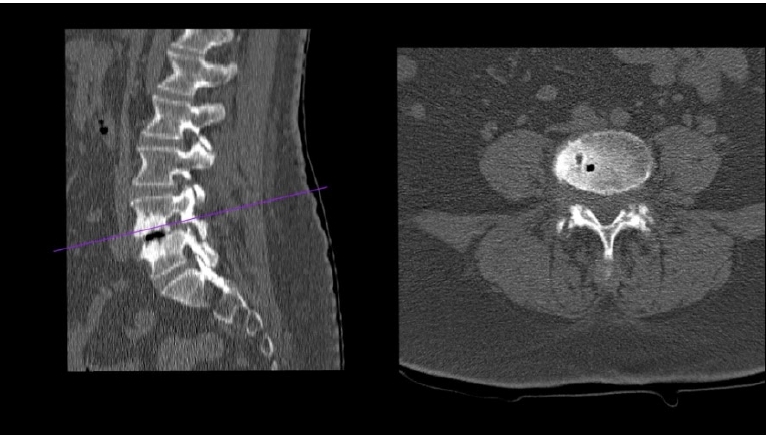

Following the initial remotion of the herniated and migrated disc, L4-L5 disc space came into view, and the slippage between both vertebral bodies became evident (Figure 5).

Following the initial remotion of the herniated and migrated disc, L4-L5 disc space comes into view.

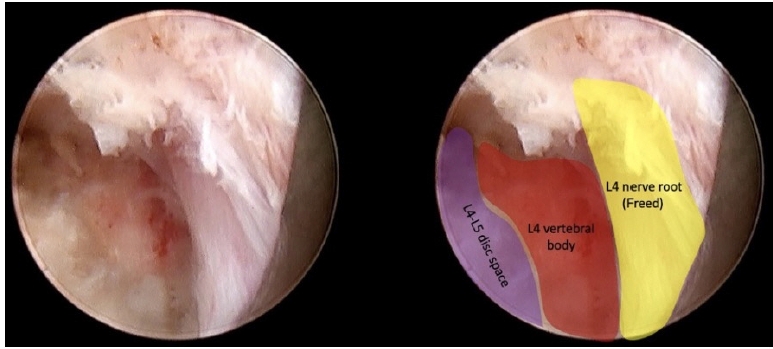

The final view showed the released L4 nerve root and the dorsal portion of the L4 vertebral body where the disc herniation was formerly located (Figure 6).

2. Lumbar Mono-radiculopathy Caused by Pure Foraminal Stenosis, with Cranio-caudal Compression

1) Case Presentation

A 77 years old female patient with 3 months old right L4 radicular pain. No lumbar pain was present.

MRI and CT scan showed a Grade II listhesis with L4-L5 right foraminal stenosis, mainly caused by L5 superior endplate and osteophyte, with severe craniocaudal compression (Figure 7, 8). Dynamic X-Rays showed stability of the segment.

2) Modules Assemble

The surgical plan included the following modules: (1) Standard SAP-based foraminotomy; (2) Osteophyte remotion; (3) Partial pediculectomy.

3) Surgical Technique

A right L4-L5 transforaminal approach was performed docking the working sheath on the L5 SAP. Thus, endoscopic navigation started at L5 SAP and following the pedicle approached the L5 endplate.

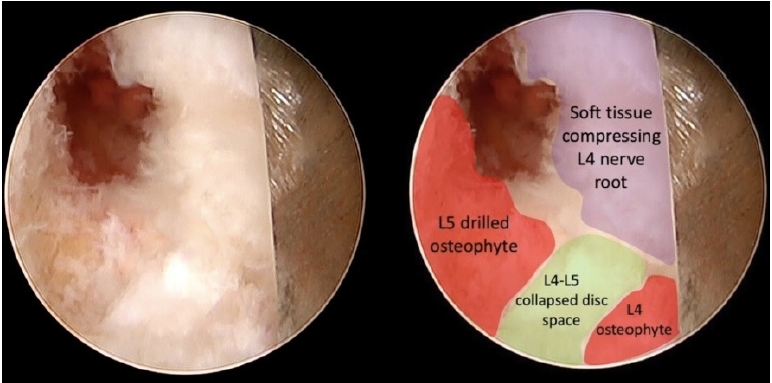

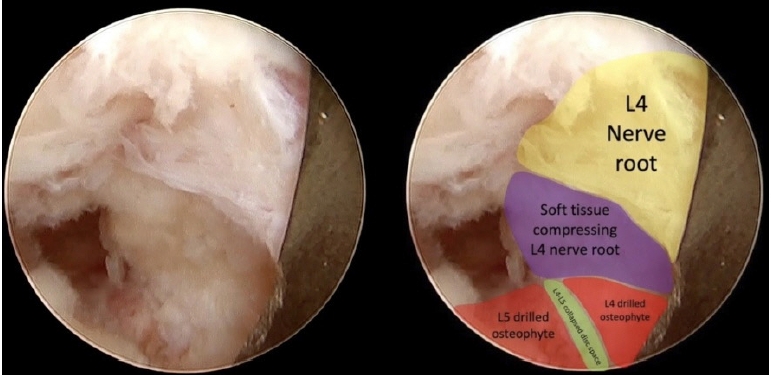

Once the right L4 nerve root was recognized and secured by turning the working sheath bevel towards it (Figure 9), drilling of the pathological L5 endplate and osteophyte was performed.

The objective was to cavitate the compressing bone and then gently fracture it with a dissector to avoid direct contact of the burr with the nerve root. After the L4 osteophyte is removed, the L4-L5 disc space becomes visible (Figure 10), and the L4 osteophyte can be removed. Finally, partial pediculectomy of the upper portion of L5 pedicle allowed complete craniocaudal decompression.

Finally, soft tissue covering the L4 nerve root was removed (Figure 11) ensuring that a tridimensional decompression was achieved.

Soft tissue covering the L4 nerve root is removed ensuring that a tridimensional decompression was achieved.

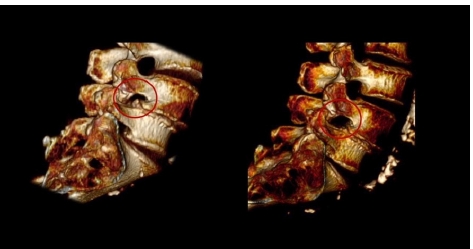

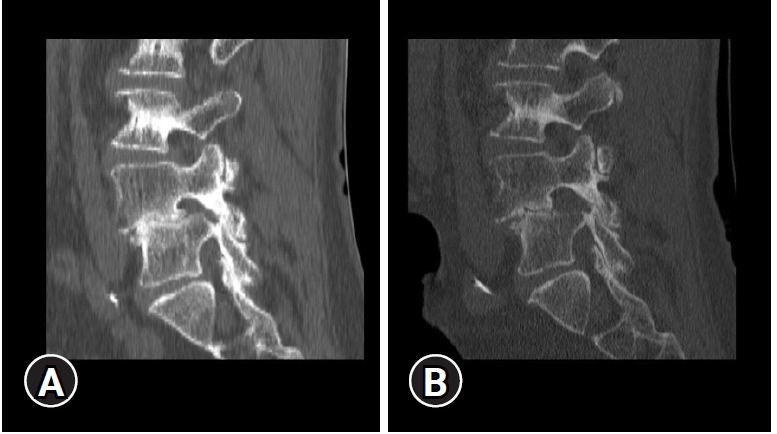

Postoperative CT scan showed restitution of cranio-caudal foraminal dimension (Figure 12, 13).

(A) Preoperative CT scan with former foraminal stenosis. (B) Postoperative CT scan showing restitution of cranio-caudal foraminal dimension.

3. Lumbar Dual-radiculopathy from Foraminal and Lateral Recess Stenosis

1) Case Presentation

A 66 years old male patient, with an 8 months history of left sciatica pain. Clinical examination revealed both left L4 and L5 affected territories. MRI showed Grade I DSL with left foraminal and lateral recess stenosis (Figure 14).

CT scan revealed that lateral recess stenosis was attributable to slipped IAP, osteophytic formations and soft disc herniation, and foraminal stenosis was caused mainly by a migrated soft disc herniation (Figure 15).

2) Modules Assemble

After clinical and imaging studies were reviewed, the surgical strategy included these modules in the following order: (1) Standard SAP-based foraminotomy; (2) Lateral recess decompression (levering maneuver); (3) Transforaminal IAP drilling; (4) Herniated disc fragmentectomy.

3) Surgical Technique

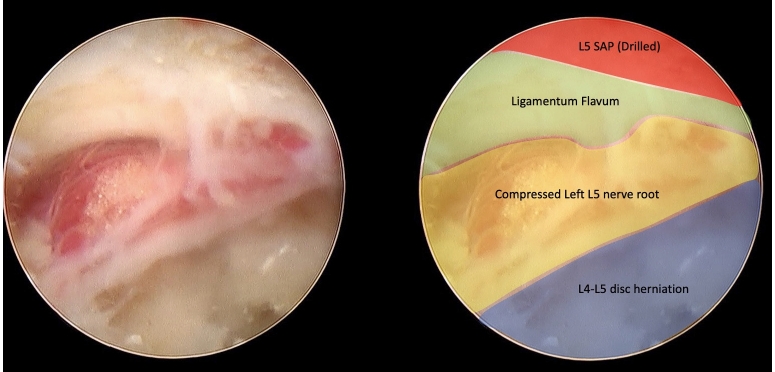

As usual, needle tip was placed on L5 SAP, with the working sheath docked on the facet’s surface. Then SAP was drilled under endoscopic visualization and using the levering maneuver, the endoscope was advanced underneath the drilled SAP into the lateral recess and slipped IAP was also drilled (“lateral to medial” rule). Once the ligamentum flavum was exposed, a partial remotion of such structure revealed the compressed L5 nerve root in the lateral recess (Figure 16).

Once the ligamentum flavum is exposed, a partial remotion of such structure reveals the compressed L5 nerve root in the lateral recess.

After removing the remaining ligamentum flavum and soft disc herniation in the lateral recess, the traversing nerve root was released (Figure 17).

Finally, following the “caudal to cranial” rule, the endoscope is moved laterally to the foraminal zone. A careful navigation towards the cranial portion of the foramen allows the removal of the remaining disc herniation to decompress the exiting L4 nerve root.

DISCUSSION

DSL affects 5%–10% of the adult population worldwide. In elderly populations (>65 years) can reach an overall prevalence of 19.1% and 25% for men and women respectively [14]. It is usually classified by Meyerding in five grades [15], according to the degree of slippage of the vertebral bodies. Despite being commonly associated with instability, DSL rarely exceeds Meyerding’s grade II [3]: As disc height decreases and facet degenerative changes advance, DSL naturally evolves to stability. But even as natural fixation is achieved, slippage can produce foraminal and/or lateral recess stenosis with subsequent nerve root compression. According to the SPORT study results, radicular pain is greater or at least equal to back pain in 74% of cases of DSL [16].

Radicular symptoms often motivate surgical interventions to alleviate neuropathic pain: as open approaches disrupt the osteo-muscular and ligament structures that maintain spine stability, the most commonly used surgical approach involves decompression and instrumentation [17]. In other words, despite DSL being a stable pathology, open surgery causes potential instability that motivates instrumentation.

In this setting, full endoscopic techniques can provide a surgical approach that effectively decompresses the neural structures while preserving stability and avoiding instrumentation.

Endoscopic foraminotomy techniques were developed in the early 2000s to treat foraminal stenosis in non-listhetic segments [18]. Technological and technical improvements allowed to increase the effectiveness of decompression and expand the approach to other pathologies [11]. However, anatomical changes associated with DSL still represent a major challenge to the endoscopic surgeon.

In this paper, we presented a module-based approach to plan and execute a transforaminal endoscopic foraminotomy in patients with DSL. Three of the most common scenarios encountered were provided as case examples.

To correctly select and assemble the surgical modules, the endoscopic surgeon must answer three main questions:

1. Which is the nerve root(s) responsible for the patient’s symptoms?

2. Where is that nerve root(s) compressed?

3. Which structure(s) is responsible for the compression?

Conducting a thorough clinical examination to identify the neural structure that is causing the symptoms is of paramount relevance in this setting: DSL is usually accompanied by other degenerative changes in the lumbar spine, and clinical-radiological dissociation is frequent: multiple stenotic segments may be evident in MRI or CT scans, but the clinical manifestations usually are more limited. In cases when the clinical manifestations are elusive, selective nerve root blocks can help in the diagnosis of the pain generator [19].

In the same way, slippage and degenerative changes present in DSL change the usual pattern of foraminal stenosis seen in non-listhetic patients: exiting nerve root can be compressed by vertebrae endplates, osteophytes, and/or disc herniations. Likewise, in cases when foraminal stenosis is combined with lateral recess stenosis, the responsible structure of the latter usually is superior vertebra IAP. These modifications demand a more refined and targeted endoscopic decompression, as well as a final revision to ensure that the nerve root has been freed in all three dimensions.

Full endoscopic surgery in degenerative listhesis. The evidence so far: Biomechanical studies have shown that transforaminal partial facetectomy has minimal impact on the biomechanics of the lumbar spine [20], and even the total endoscopic removal of the facet joint has less consequences than open laminectomy [21].

Specifically in patients with DSL and stenosis, the concept that decompression without fusion can be advantageous has been established in the spinal surgery community for several years. Minimally invasive spine surgery such as tubular techniques, or even open surgery approaches to the lumbar spine have proven to be successful in managing stenosis in patients suffering DSL without fusing or compromising spinal stability [22]. This notion motivated the hypothesis that, being endoscopic spine surgery a less invasive method than open surgery, endoscopic decompression would be effective in patients with lumbar stenosis and concomitant DSL. Starting in 2015, Yeung published a series of level 4 and level 5 evidence-based medicine opinion articles about the author’s experience with endoscopic foraminotomy in patients with DSL [23-26]. Despite lacking methodological rigor and statistical analysis, the richness of the texts illustrates the rationale behind the author’s experience.

Nevertheless, high-level evidence respecting endoscopic foraminotomy in degenerative listhesis is limited. Published papers about this specific topic include mainly case reports and case series with short follow-up periods. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis regarding endoscopic lumbar foraminotomy included only 14 studies with a total of 600 patients (without taking into consideration case reports) [27]. Of those 14 studies, only one included patients with spondylolisthesis [18].

The terminology barrier: The evidence concerning endoscopic lumbar foraminotomy is not only scarce but also severely fragmented into multiple terms for similar, if not the same, procedures. Foraminoplasty, foraminotomy and transforaminal decompression often relate to the same surgical goal: visualize and decompress the exiting nerve root passing through the foramen. To homogenize this and others multiple terms, in 2020 a “Global Consensus Paper on Nomenclature for Working-Channel Endoscopic Spinal Procedures” was published [28], suggesting to unify all the previous denominations under “Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Foraminotomy”. However, this process will only affect future publications and is expected to take several years to complete. For that reason, when conducting literature search regarding this topic it is advisable to include multiple terms.

For example, Cheng et al. [29] presented in 2020 a case series of 40 consecutive patients with DSL who underwent transforaminal endoscopic decompression (transforaminal endoscopic lumbar foraminotomy). Follow-up period ranged from 12 to 24 months, with 87.5% of patients achieving a good-to-excellent outcome according to modified MacNab criteria. Interestingly, the vertebral slippage before surgery and after follow-up period was not significantly different. This study and its conclusions was not included in endoscopic foraminotomy meta-analysis because the terminology used to describe the procedure eluded the database search.

CONCLUSIONS

Transforaminal lumbar endoscopic foraminotomy represents a minimally invasive technique to treat foraminal and combined foraminal-lateral recess stenosis. DSL and its multiple scenarios represent a challenge to the endoscopic surgeon. Module-based approach can help systematize and execute these demanding endoscopic procedures. Due to its muscle, facet joint and ligament sparing nature, case series suggest that it would not alter segmental stability in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis. However, powerful and well-designed studies are needed to accurately prove this statement.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.