Fundamental Concepts of Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MISS) and Purpose to Pursue

Article information

Abstract

Minimally invasive techniques are currently applied in large variety of spinal surgical procedures. Surgical invasiveness has been minimized mainly for surgical accesses but in some procedures (e.g. decompression surgery) also for the ‘target surgery’. Despite different techniques, there are general principles which have to be considered. Only with combination of preoperative planning, the (educational) elaboration of a surgical strategy, the thorough knowledge of the patient’s individual anatomy, the respect for the anatomy, properties and function of tissues, the well-trained surgeon, and the use of modern surgical high-tech — equipment will lead to an improvement of peri- and postoperative morbidity and clinical result for our patients. Minimally invasive spine surgery is a ‘moving target’ so it must be accepted that evidence Level I data in a scientific sense are still missing for some of these procedures. However, empirical data all suggest that minimally invasive spine surgery can significantly improve early post-op outcomes and decrease perioperative morbidity. It is thus the task of every spine surgeon to apply his experience — based expertise in a responsible way for the safety of our patients. Minimally invasive spine surgery is nothing but a ‘natural evolution’ of surgical technique to further decrease tissue trauma for certain operations.

INTRODUCTION

One of the historically based fundamental principals of any kind of ‘invasive’ surgical treatment has always been to reduce ‘iatrogenic’ tissue trauma to a minimum.

The ‘first do not harm’ —philosophy which dates back to Hippokrates (460-370 B.C.) has always been the guidance for surgical treatment.

As surgeons we have to be ‘invasive’ to cure the patients’ disease or pathology and to improve his symptoms.

To do this adequately we have to follow 2 principle rules:

1. Achieve the surgical goal (e.g. decompression of a nerve; fusion of a motion segment; replacement of a disc etc.)!

2. Do no harm to the patient.

In order to achieve this second goal, 3 facts are important which are:

1) assessing the risk of the procedure preoperatively

2) keeping the collateral damage low during surgery

3) avoiding complications.

In spinal surgery, as in other surgical specialties, the last two and a half decades have been the decades of minimally invasive surgical procedures. Technological advances such as imaging techniques, new materials, implants and equipment, computer-assisted navigation etc. have shifted surgical technique into a new dimension.

1. Achieve the Surgical Goal

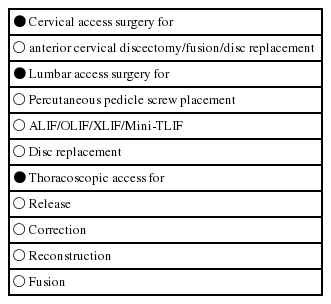

Each surgical procedure has a goal, which is to solve the patients clinical problem in attacking the underlying pathology. This pathology is the target of every surgical procedure. So one of the goals of MISS is to do an efficient ‘target surgery’ with a minimum of iatrogenic trauma. To reach the target, the surgeon has to create an access to it. So practically spoken, either the ‘access’ — part and/or the ‘target’ —part of the surgical procedure itself can be minimally invasive (Tables 1 and 2).

The majority of minimally invasive techniques in spinal surgery refer to the ‘access’ —part and not primarily to what is done in the target region (e.g. minimally invasive fusion techniques).

2. Do No Harm to the Patient

The Hippocratic principle has to be applied when it comes to the indication for minimally invasive surgery (e.g. is the patient/the pathology suitable for a minimally invasive procedure?) as well as for the preoperative risk assessment.

2.1 Preoperative Risk Assessment

2.1.1 General considerations

The majority of minimally invasive spine procedures are still not (yet) considered as being current standard procedures and thus sometimes cannot be found (yet) as part of surgical textbooks or surgical teaching. Some of these procedures are really innovative and are still part of ongoing clinical trials. In practice this means that surgeons who want to adopt new techniques inevitably go through a learning curve. In practicing surgical techniques on the patient means that we as a surgeon are the biggest risk factor!

To take the risks of a new operation in a responsible way, we have to be prepared. I can give the following advices:

Get an adequate training. Watch the masters doing such operations. Don’t overestimate your expertise and technical skills. Stay self-critical and start with easy cases. Monitor your results.

Several publications deal with MIS learning curves and as a rough measure we can say that you need between 50-100 cases until your learning curve reaches the plateau phase [1-3].

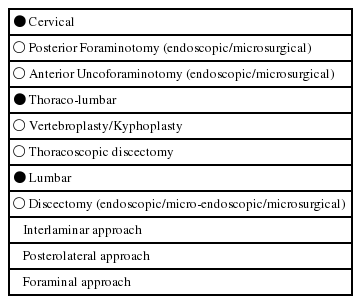

2.1.2 Preoperative planning of access surgery (Table 3)

Topography and volumetry of the surgical target must be clear. These informations are usually given by different imaging techniques such as MRI, CT scan etc. Especially in anterior approaches to the spine, knowledge of the topography of the prevertebral space can be valuable. Retraction of the prevertebral blood vessels is an important surgical step to expose the anterior circumference of the lumbar spine. Minimally invasive approaches usually do not allow a wide exposure and mobilization of these vessels. This can increase the risk of indirect damage to branches entering in or exiting of the arteries and veins. Preoperative vascular topography can be determined with the help of colour-coded 3-D-CT scans which give a clear picture of the individual anatomy (Fig. 1).

3 D color-coded CT angiography to show the surgical topography of retroperitoneal blood vessels and the anterior lumbar spine.

Interestingly the rate of vascular complications of anterior approaches to the lumbo-sacral spine has dropped significantly if you compare patient series from the early 1990’s to those from first decade of this century [4].

The spine as the central ‘axis’ organ can be reached from different directions through different entrances. The surgical entrance (= skin incision) must be determined by the topography of the target —and the access anatomy. It should be adequately placed and should have an adequate (smallest possible) size. Cosmetic aspects should be considered (e.g. skin incision follows skin lines). Traces of previous operations in the access region can also influence the access strategy.

The surgical route to the target area should be least traumatic, i.e. it should strictly follow anatomical pathways such as preformed spaces, or (if this is not possible for the whole skin-target-distance) it should be performed with a minimum of collateral damage to surrounding tissues. If collateral damage cannot be avoided, it should be reparable or at least negligible for the clinical outcome. If possible, the integrity and function of the surrounding muscles (abdominal, cervical, paravertebral) should be preserved.

The most important aspect is the adequate exposure of the target area. The target (e.g. disc herniation, disc, spinal nerve, tumor etc.) should be clearly visible and identified. The target treatment (e.g. discectomy, vertebrectomy, neurolysis, tumor removal) should be possible without any restrictions due to the small approach. Spinal manipulation (e.g. reduction-maneuvers) should be possible as well as the insertion of implants for spinal stabilization.

The retreat from the surgical field should leave no or only minor ‘traces’ (e.g. hematoma, ‘open annulus fibrosis following discectomy, scar tissue) and it should not be relevant for the outcome (e.g. muscle damage). In case of a staged surgical therapy (e.g. dynamic posterior stabilization) or in cases were there is a possibility for a recurrent pathology (e.g. disc herniations) the postoperative traces such as scar tissue, muscle — or intervertebral joint damage should not negatively influence these further therapeutic options.

To achieve all these goals, meticulous preoperative planning is necessary.

2.2 Keeping Collateral Damage Low and Avoiding Complications

2.2.1 Positioning of the patient

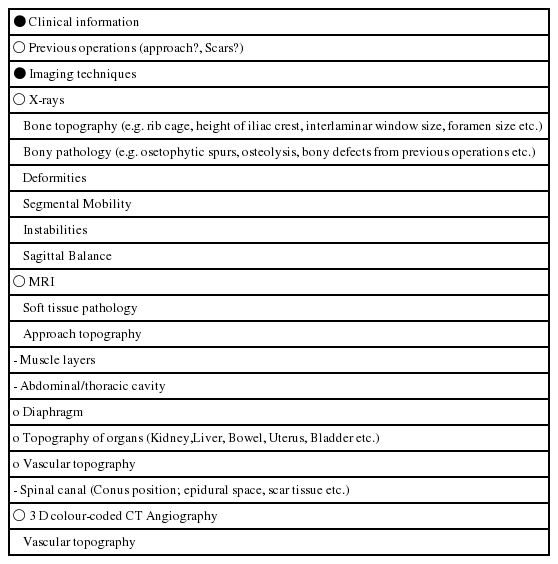

Positioning of the patient on the operation table requires modifications. Localization of entry area under fluoroscopic control is mandatory and surgical preparation techniques must be adapted. Positioning of the patient can strongly influence the minimally invasive exposure as well as the target surgery. Examples are the lateral positioning and access to the lumbar levels L2-L4 for anterior lumbar interbody fusion which eases the access to the spine even in obese patients for ALIF, OLIF or XLIF approaches (Fig. 2). Another example is the knee-chest position of patients for lumbar microsurgical discectomy or decompression procedures which leads to a pressure release in the epidural venous system and thus diminishes the risk of epidural bleeding (Fig. 3).

Lateral positioning of the patient for OLIF or XLIF approach. In this position, the abdominal contents follow gravity and shift away from the surgical approach corridor.

2.2.2 Localization of skin incision

Skin incisions are supposed to be small in minimally invasive spine surgery. This implies an adequate localization as referred to the target area. In the majority of mini-open techniques, the skin incision is placed directly above the target. In endoscopic techniques, the localization of the incision(s) is determined by the intended working direction as well as by the view angles necessary during the operation.

2.2.3 Surgical dissection techniques

To minimize tissue trauma is the paramount goal of MISS. Traditional surgical techniques show striking differences between the surgical dissection and handling of different tissues (e.g. nerve versus bone; muscle versus blood vessel). The increasing knowledge about structure and function of tissues requires a modification of traditional surgical dissection techniques. A muscle or a bony structure should basically be treated with the same care as a nerve or a blood vessel. Blunt, muscle splitting techniques are characteristic for MISS. Special instruments, light — and magnification sources (loupe, surgical microscope, endoscope, headlamp) as well as retractor devices (e.g. frame — or ring-retractors, tubes etc.) are necessary.

The use of high speed burrs instead of large rongeurs can preserve bony structures. The individual mobilization of blood vessels can decrease the vascular complication rate (Fig. 4).

Different ways to mobilize the retroperitoneal blood vessels for MIS anterior approach to the level L4-5.

The use of hemostatic agents in spinal canal surgery can reduce the risk of epidural hematoma. The microsurgical closure of the annulus fibrosis is supposed to improve the low healing potential of this structure.

2.2.4 Instruments and implants

Minimally invasive spine surgery is not possible without optical aids. Light and magnification are needed to illuminate and visualize the surgical target in the depth of the human body through small skin incisions. The minimum affordings are headlamps and loupes. The surgical microscope and/or endoscopes are helpful or mandatory for certain techniques. Surgical instruments need to be bayonet-shaped and/or long enough to bridge the distance from the skin to the target. The branches of instruments for electro-coagulation must be isolated to avoid tissue damages in the access region. One of the major challenges for the next years will be the further improvement of instruments and implants which allow for intraoperative spinal manipulation (reduction, correction) and fixation. Last but not least, tubes or frame-type retractor systems are mandatory to keep the surgical corridor open.

3. What is a MISS Procedure?

When we talk about invasiveness we must distinguish between different surgical steps. In some procedures the definition of ‘minimally invasive’ is only true for the access part. A minimally invasive anterior fusion (e.g. ALIF, OLIF, XLIF) still implies removal of the disc and replacement with an implant. Although the access to the motion segment is minimally invasive, the surgery at the target is the same as in open fusion procedures.

However, there are procedures which have been completely transformed into minimally invasive techniques, such as discectomy or decompression procedures (see Table 2). They are truly minimally invasive because not only the access but also the surgery in the target region (e.g. removal of disc fragment, dome-shaped decompression of the spinal canal) have become definitely less invasive as compared to wide laminectomies.

It is important to remember this and also to communicate this to our patients that a small stab-incision in the skin does not necessarily mean that it was a ‘small operation’.

4. Purpose to Pursue

For those of us who had the honor to be part or protagonists of MISS-developments, it is without any question that spine surgery will sooner or later transform into a minimally invasive specialty. Even today more than 75% of our surgical procedures are performed with minimally invasive techniques or at least certain surgical steps are done with this technique.

There are 4 strong arguments why minimally invasive techniques will in the end dominate spinal surgery.

4.1 The Surgical Goal can be Achieved with Less Iatrogenic Trauma

This is true also for other MIS procedures (e.g. knee surgery). The extent of tissue trauma can be measured. Analysis of acute phase proteins such as C-reactive protein, of muscle proteins (e.g. Myoglobin), enzymes (e.g. Creatinphosphokinase, Lactatdehydrogenase) or Interleukines can give us a clear picture about the amount of tissue trauma which is produced during a surgical procedure. It has been shown in numerous publications that these tissue parameters are significantly lower with less invasive procedures [5-12].

4.2 The Surgical Goal can be Achieved with Less Complications

There is growing evidence that minimally invasive spine surgery can reduce complications rates such as vascular complications [4]. A recently published study suggests, that minimally invasive discectomy, decompression and mini-TLIF techniques lead to marked reduction of surgical site infection [13].

The reasons for the reduced vascular complications and infection rates however may be different. Whereas the reduced vascular complication rates are most probably the result of a more meticulous surgical planning including imaging of vascular topography, the reduced infection rates seem to be due to less tissue exposure and reduction of contamination areas.

CONCLUSION

What we have seen in the last decades of spinal surgery is a ‘natural evolution’ of surgical technology towards better techniques which produce less tissue-trauma but still achieve the goal of the specific surgical procedure. This development follows exactly the universal ‘First do no harm’- concept’ of any surgical specialty.

We may call it ‘minimally invasive surgery’ now, but sooner or later this term will disappear because this technology will become common ‘standard’.