Get Ready for 100 Years of Active Spine Life Using Percutaneous Endoscopic Spine Surgery (PESS)

Article information

Abstract

Lumbar spinal stenosis is the most common indication for spinal surgery in patients older than 65 years. After the introduction of Kambin's safety triangle, percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery has started through transforaminal approach for discectomy and is now being extended to spinal stenosis through interlaminar approach, which is an important part of the degenerative spinal disease. With the increase in human longevity, the development of effective treatment for degenerative diseases is inevitable, and future percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery (PESS) will play a very important role in maintaining the health of this ‘super-aged’ population. Endoscopic techniques impart minimal approach related disruption of normal spinal anatomy and function while concomitantly increasing functional visualization and correction of degenerative stenosis. Advantages of full endoscopic spine surgeries are less soft tissue dissection, less blood loss, reduced hospital admission days, early functional recovery and enhancement in the quality of life. With proper training and advancement in equipment and technologies, percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery will be able to successfully treat the aging spine.

INTRODUCTION

The fields of spine surgery have experienced rapid growth over the past decade, yet little research has focused on the issues related to older age. Perioperative complications are frequently encountered in elderly patients owing to comorbid cardiovascular and renal disease, poor nutritional status and immobility. Concerns regarding perioperative complications may be allayed by decreasing the invasiveness with which the spine is approached. Smith and Fessler [1] have mentioned without exaggeration about the paradigm change in spine surgery accompanying the evolution of MISS (Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery) techniques. Ideal surgical approach to the spine is the one, which causes minimal approach related disruption of normal spinal anatomy and function.

Full endoscopic surgical approaches to the spine differ from other minimally invasive surgical techniques due to the unique technical qualities of the spinal working endoscope. Use of spinal endoscope facilitates the principles of minimally invasive spinal techniques by allowing the specialist to visualize spinal structures in magnified view [2]. This magnified view facilitates surgical treatment with minimal surgical damage to normal anatomical structures.

Initially, standard endoscopic surgical techniques were restricted to the lumbar, cervical and thoracic disc herniations [3]. Recent advances in endoscopic optical innovation and surgical techniques allow the care and treatment of other spinal conditions including central and foraminal stenosis decompression of the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine including anterior cervical decompression [4-7].

Advantages of full endoscopic spine surgeries are less soft tissue dissection, less blood loss, reduced hospital admission days, early functional recovery and enhancement in the quality of life [8]. With the increase in human longevity, the development of effective treatment for degenerative diseases is inevitable, and future percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery (PESS) will play a very important role in maintaining health of this ‘Super-aged’ population.

HISTORICAL REVIEW

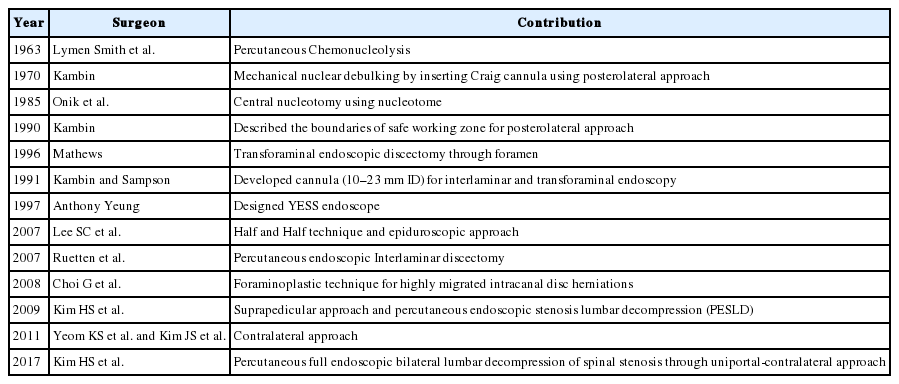

Albert E. Telfeian et al. [9] divided the history of endoscopic spine surgery into 3 phases: inspiration, invention, and innovation. The inspired early spine surgeons desired an endoscopic spine surgery for accessing lumbar disc herniations, which would be less invasive than conventional open surgical techniques. They approached the disc pathology through Kambin’s triangle. The invention would then be required in the armamentarium to make endoscopic discectomy a feasible and then a successful procedure. With more than 50 years of nitty-gritty (Table 1), the innovators now have the inventory and learning experience to treat various spine issues besides the herniated lumbar disc prolapse for which this technique was proposed.

NEED TO APPROACH THROUGH KAMBIN’S TRIANGLE

1. Complication of the Conventional Open Surgery

In the literature, the incidence of spine operations has increased than before in patients of age 65 and above. Distinctively, in a 2010 report, a 28-fold rise in spine fusion surgeries was observed for elderly patients. Elderly patients with more co-morbid factors, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease (prior procedures), depression, and obesity, experience higher postoperative complication rates and expenditure [10]. In literature comparing three operative methods for different age groups with degenerative scoliosis and radiculopathy with minimum 2-year follow-up [11]. In patients with average age of 76.4 who underwent lumbar decompression alone, the complication rate was 10%. In patients with average age of 70.4 years who underwent decompression/limited fusion (1-2 levels), the complication rate was 40%. Nevertheless, for those averaging a lower 62.5 years of age with multilevel full-curve fusions, the highest complication rate of 56% was observed. In conclusion, had the average age for the latter group been higher, the complication rate would have risen even further. Notably, the less extensive procedures (decompression alone or decompression with limited fusion) yielded considerable enhancement on the postoperative Oswestry Disability Index, while the full fusion group did not.

2. Need of Structural Preservation Spine Surgery

The prime purpose of improving pain and neurological deficit in the practice of spine surgery is shifting to a more ambitious goal, namely to improve the overall quality of life and the future of patients through three key measures (1) preserving the intraspinal anatomical structures; (2) preserving the paraspinal anatomical structures; and (3) preserving the functionality of the spinal segment. Thus, three new concepts have emerged (a) minimal surgery; (b) minimal access surgery; and (c) motion preservation surgery. These concepts are covered in a new term, minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS). The term "MISS" is not about one or several particular surgical techniques, but a new way of thinking, a new viewpoint and a new philosophy [12]. Even if the advancements in minimally invasive spine surgery are recent, its application includes all spine segments and almost all the existing conditions.

3. Kambin’s Triangle - True Minimized Option for Degenerative Lumbar Disc Herniation

Direct access to the disc through transforaminal approach, was advanced and universalized by Prof. Anthony Yeung, and symbolize the first major accomplishment of percutaneous endoscopic discectomy. Transforaminal discectomy through posterolateral approach uses the natural anatomical window of the intervertebral foramen to minimize damage during approach. The working cannula exceeds through muscle planes, passes through the foramen and between the exiting and traversing nerve roots (Kambin’s triangle) to enter directly into the disc [13]. Using this approach neither cutting of muscle nor resection of bone or ligament is required during discectomy.

The transforaminal approach provides direct access to the disc for nuclear decompression and annuloplasty. After withdrawing the working cannula from the disc, structures outside the disc can be easily accessed for foraminoplasty or for removing a sequestered disc fragment. Additionally, by changing the skin entry point and the angle of approach, different disc levels can be accessed using the same incision [14].

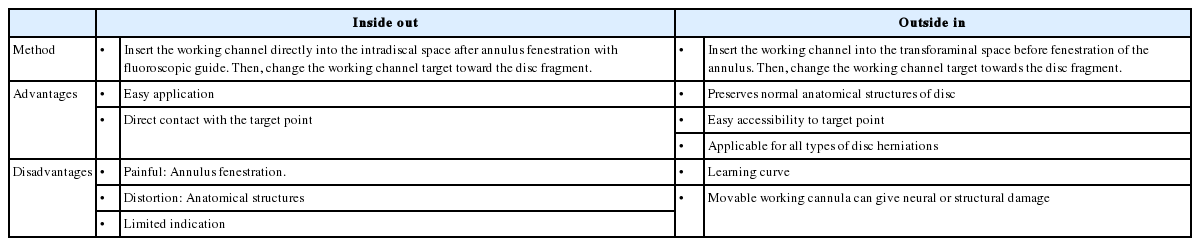

INSIDE OUT APPROACH AND OUTSIDE IN APPROACH

Depending on how the pathology is approached, posterolateral techniques can be classified into “inside-out” and “outside-in” techniques (Table 2). The inside-out techniques such as the YESS technique starts working within the disc [15,16]. If needed, the working system can be repositioned so that the tip of the working cannula is located in the foramen or the spinal canal. The inside-out techniques are suitable for treating internal disc disruption, disc tears and bulges, and pathologies located in the foramen or spinal canal. But for minor disc pathologies, especially when the pathology is not located within the disc, inside-out techniques may cause too much damage by removing normal disc tissue.

For the outside-in techniques, the opening of the working cannula is initially positioned in the foramen or epidural space and then pushed to the inside the target disc, if needed [17,18]. The outside-in techniques work well when treating foraminal disc herniations and extraforaminal disc herniations [19]. But the technique may demand an aggressive undercutting of the facet with drill tools to reach centrally located disc herniations at L5-S1, posing a risk of damaging the nerves and dura. For both inside-out and outside-in techniques, it is challenging to treat spinal pathologies located at the L5-S1 level, especially in male patients because of the interference of the iliac crest.

APPROACH: LESS ANGLED OR POSTEROLATERAL

As compared to posterior lateral approach, the less angled extreme lateral approach has following advantages.

1. It approaches the epidural space directly; cutting of normal annulus fibrosus is not required [20]. The cutting of annulus fibrosus causes severe pain during surgery and persistent pain after surgery. Moreover, this is one of the leading causes of recurrence after surgery.

2. It allows excision of central disc herniations by approaching in parallel with the posterior longitudinal ligament.

3. As this approach uses epidural space which provides an increased vertical range to manipulate the endoscope than the posterior lateral approach and allows excision of high migrated disc herniations [21].

However, the less angled approach has the potential for visceral damage and to some extent the possibility of exiting nerve root injuries so this approach is not used widely at present. Additionally, the less angled approach can be used effectively with the lever technique [22] or outside in procedure and it must be considered in terms of procedure safety.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATION OF PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC SPINE SURGERY

1. Three Different Approach Routes

Since the conventional inside-out technique approaches only the intervertebral route, it is difficult to remove the disc if it is migrated superiorly or inferiorly. However, there are three different routes in the transforaminal space anatomically, and if used effectively, percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery can be applied to a wider range of lumbar disc herniation.

Central, paracentral, and high canal compromised LDH were approached by the intervertebral route; foraminal, superiorly migrated and far lateral LDH were approached by a foraminal route (Fig. 1) and inferiorly migrated LDH was approached by suprapedicular route [23].

2. Overcome the Anatomical Limitation using the Evolution of the Endoscopic Drill

One of the main anatomical barriers of the transforaminal area is the bony structures. In recent years, the developments in endoscopic drill have solved this problem. The use of a high-speed drill under clear endoscopic visualization facilitates safer and more efficient bone removal (Fig. 2). With the articulating bone burr, we can change the drilling direction and cover up more working area. After the undercutting of the hypertrophied facet and part of the pedicle, the remaining bony work and soft tissues can be cleared using endoscopic punches, forceps, and a laser [24].

3. Transforaminal Approach Vs Interlaminar Approach

The conventional percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar approach is similar to microscope-assisted surgery because of removal of ligamentum flavum and cutting of annulus. Therefore, the transforaminal approach has been preferred in terms of minimizing invasive surgery. Although many techniques of PELD (percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy) have been introduced, most studies at the L5-S1 level have preferred the interlaminar approach [25,26]. It is thought that the high iliac crest, narrow foramen, and a large facet joint are a barrier to performing transforaminal PELD. On the other hand, Yeung and Tsou [16] suggested that PELD could access all lumbar levels, even L5-S1. The favorable approach for L5-S1 level by endoscopic route has been a matter of debate for long. However, a surgeons preference for the interlaminar or transforaminal route, in addition to the height of iliac bone continue to remain an important factor in this decision.

4. Importance of Interlaminar Approach

Percutaneous endoscopy lumbar discectomy has an anatomical limitation for endoscope insertion, and there are two main surgical approaches: interlaminar and posterolateral. The endoscope insertion for posterolateral approaches is a blind procedure, but it can be safely achieved via the Kambin’s triangle [27]. During the interlaminar approach, structural damage includes not only ligamentum flavum but also paraspinal muscle and bony structures. Through structural preservation PEILD [28], it is possible to avoid this damage (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the insertion of the cannula for the interlaminar approach is performed under endoscopic visualization, but it is impossible to completely avoid direct retraction of the nerve root and/or dural sac by operative instruments. From previous experience with an open, microscopic, or microendoscopic discectomy, we recognize that some extent of transient retraction of the nerve root is acceptable. Nevertheless, we have to minimize the retraction as much as possible. In the meantime, the importance of the interlaminar approach has not been recognized as it is focused on solving some problems that the transforaminal approach cannot solve. However, the importance of the interlaminar approach is reappearing, as it is the basic approach for percutaneous endoscopic decompression.

5. Goals of Application of Percutaneous Endoscopic Spine Surgery in the Degenerative Spinal Disease

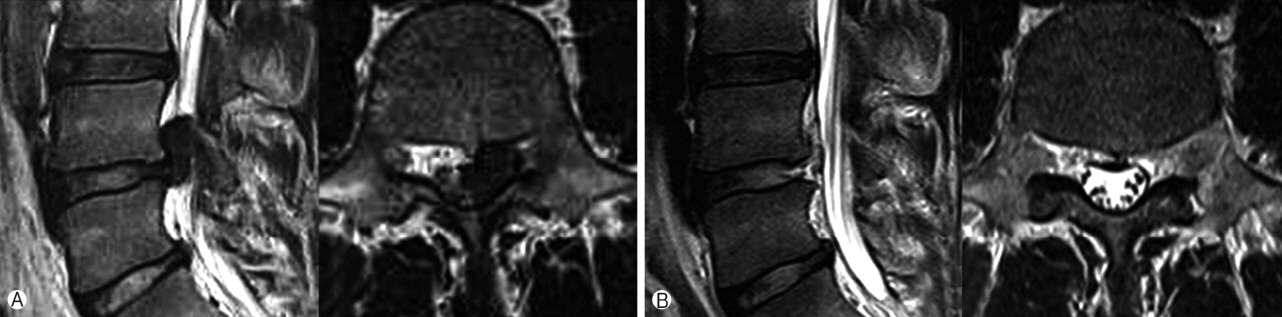

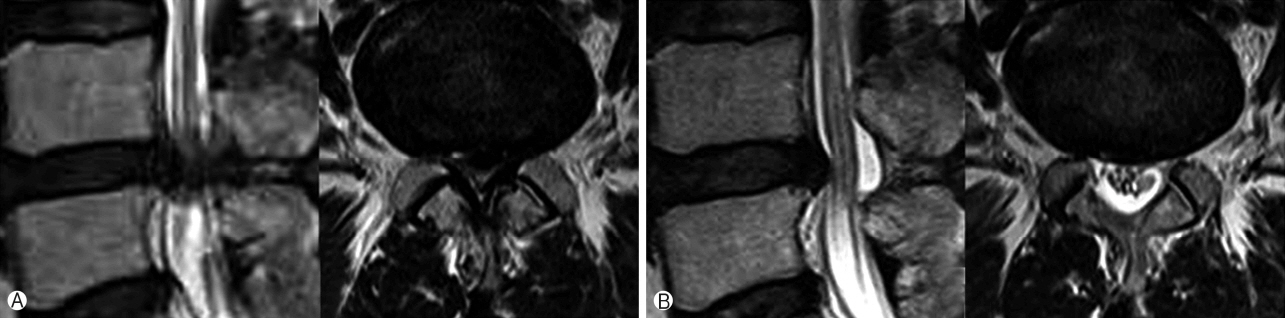

However, it is important to be aware of the fundamental purpose of percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery. In this respect, the pathophysiology of disc herniation and spinal stenosis and the concerns about the purpose of treatment according to each pathophysiology will provide a basis for this. In other words, the main pathology of lumbar disc herniation is nerve root compression [29] and it is considered that the most effective treatment can be achieved if it is effectively removed without any other peripheral damage. However, the pathologic hypertrophied ligaments, bony structures and vascular condition around the neural structure is the main cause of spinal stenosis [30] so it is necessary to effectively remove the surrounding pathologic anatomical structures while maintaining sufficient spinal stability (Fig. 4).

Sixty-one years old female with back pain and Left leg pain (VAS 8) more than 6 months. With Left L5 weakness of grade 1. Ⓐ Preoperative MRI, Ⓑ Postoperative MRI.

The first goal to perform percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery is structural preservation procedure, preservation of functional segment being the second goal and rehabilitation for normal return to life is the third goal.

FUTURE OF THE PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC SPINE SURGERY

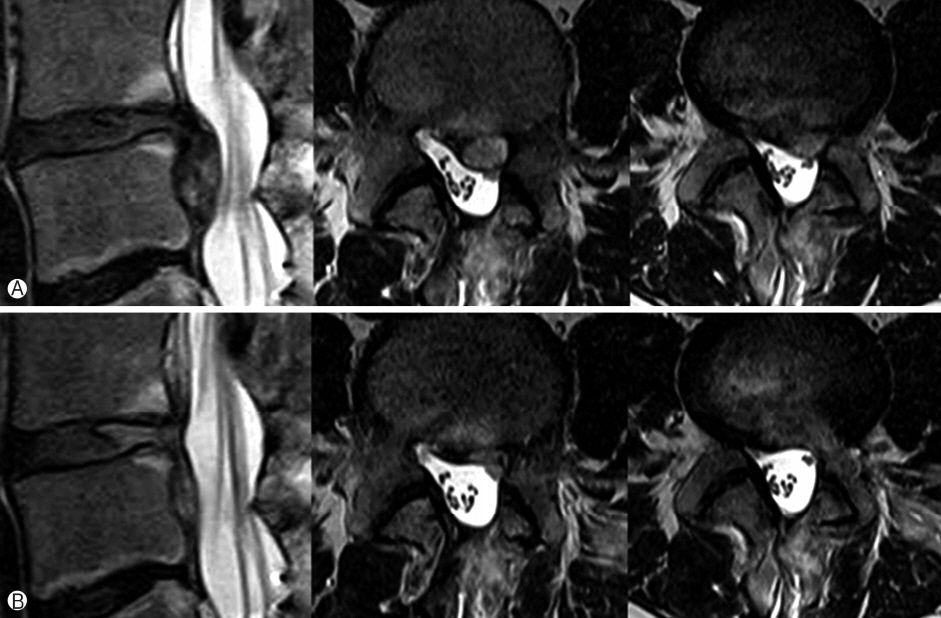

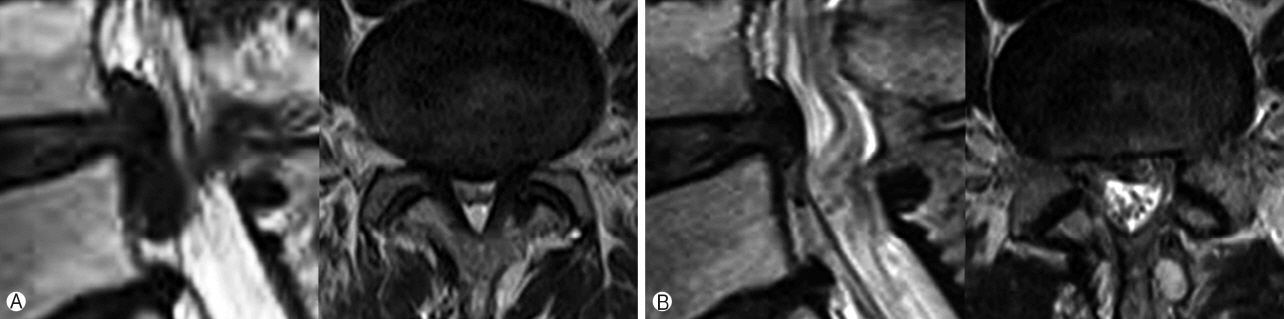

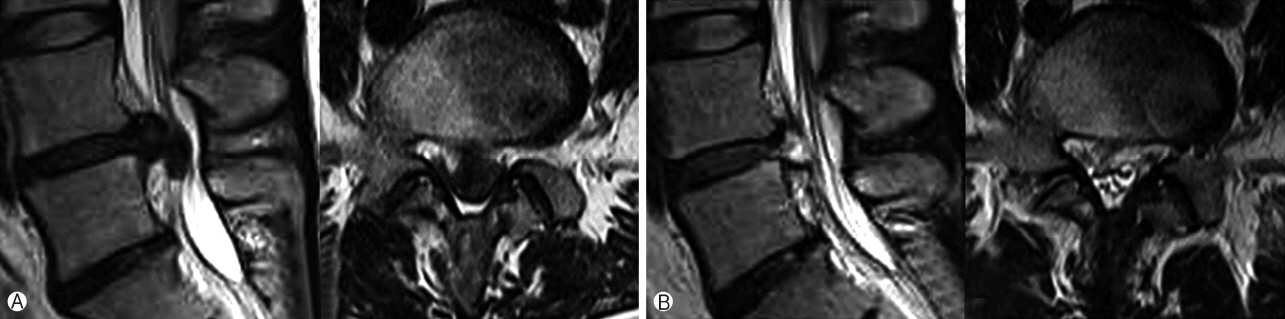

1. Application in Patients with the Severe Neurological Deficit

There is a limitation in the application of percutaneous endoscopy in patients with the severe neurological deficit. More surgical expertise and development in armamentarium is required to increase the spectrum of endoscopy in these patients (Figs. 5, 6).

Thirty-six years old female with left foot drop (L4: G0, L5: G0). Ⓐ Preoperative MRI, Ⓑ One day postoperative MRI after percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy. Patient motor weakness recovered completely 4 months after the operation.

2. Learning Curve

The learning curve of the transforaminal approach is steep and easy to learn, while the learning curve of the interlaminar approach is flat and hard to master [31]. Surgeons willing to spend the time and energy necessary to gain proficiency in endoscopy can expect to be rewarded through the benefits provided to their patients.

3. Safety Control

In future endoscopic spine surgery is expected to be more widespread. It is planned to execute surgeries with better imaging systems and with 3D images [32]. At the same time, in order to enhance the sensitivity of the hand movements of surgeons and lessen the complication rates, it is expected that robotic surgery will be used in endoscopic spinal surgeries.

4. Healthy Spine Life

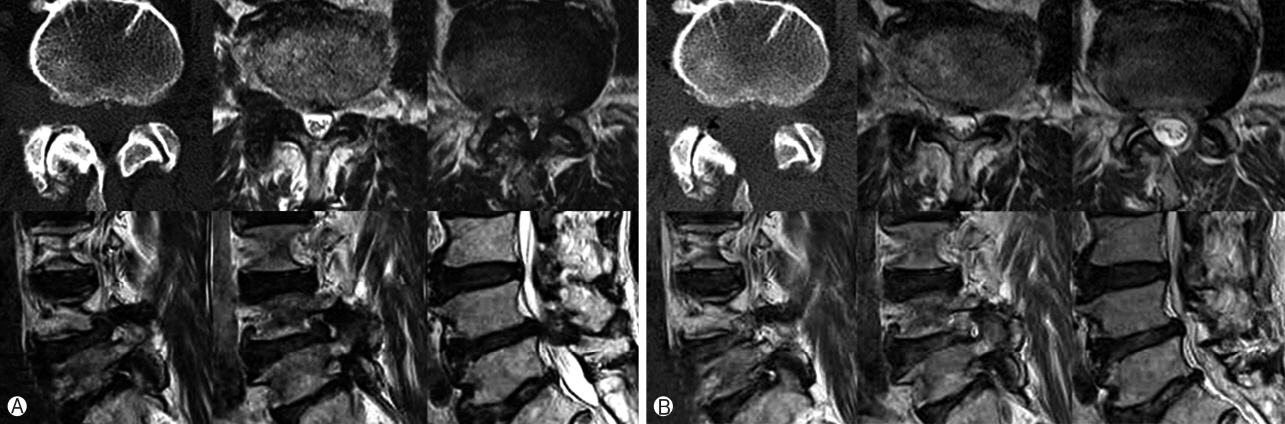

Endoscopic spine surgical technique has become more practical and standardized. Therefore, this technique may offer more reliable and reproducible results, especially for elderly or medically compromised patients to maintain healthy spine life (Fig. 7).

Seventy-year-old male with low back pain, neurological intermittent claudication and both leg radiculopathy (R>L). Preoperative MRI (Ⓐ) showing central spinal canal stenosis and foraminal to far lateral disc prolapse at right L4-5 level. Postoperative MRI (Ⓑ) after endoscopic decompression and discectomy showing sufficient decompression without violation of facet joint as demonstrated on CT scan.

CONCLUSION

Percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery has evolved over the past several decades and is emerging as an important method of spine therapy for humans who want a healthy 100-year-old living in the future. However, it is true that the lack of necessary training courses and the development of equipment and technologies are still weak. In the future when these problems will be solved and percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery will be able to treat all problems of aging spine.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge scientific team members Ms. Jae Eun Park and Mr. Kyeong-rae Kim for providing assistance in acquiring full text articles and managing digital works.