INTRODUCTION

Direct anterior screw fixation described by Böhler and Nakanishi in 1982 has gained popularity as the treatment of choice for selected cases of type II odontoid fractures [1,2]. The advantage being restoration of the C1–C2 rotatory movement, this technique uses the C2–C3 interspace and the inferior aspect of C2 as the entry point for the odontoid screw [3]. Congenital fusion of C2–C3 in this setting poses a unique challenge in performing this procedure in view of a longer and curvaceous trajectory. The patient described in this case report successfully underwent an anterior screw fixation in type II odontoid fracture in the background of congenital C2–C3 fusion.

CASE REPORT

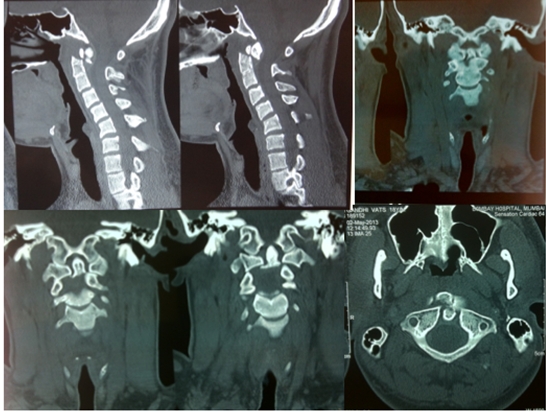

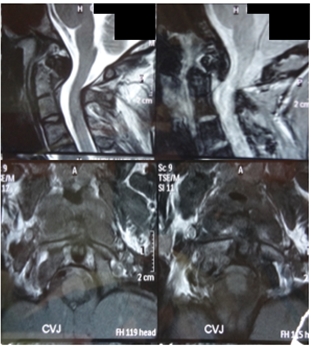

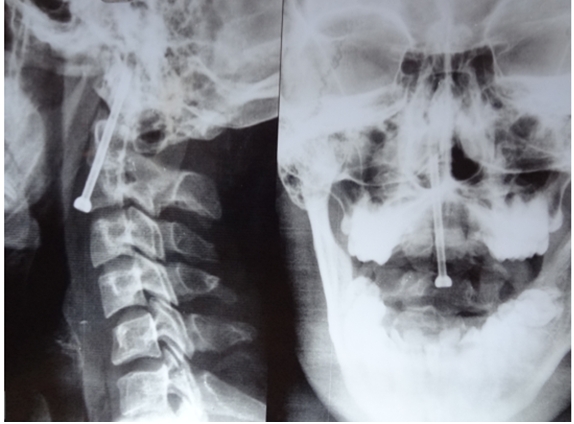

An 18-year-old male presented to the emergency department after a car accident with neck pain and difficulty in turning his neck. Clinical examination entailed no focal neurological deficits. CT scans revealed a Type II odontoid fracture with 6mm posterior displacement and congenital fusion of the C2–C3 vertebral body (Figure 1). MRI revealed absence of cord injury (Figure 2). A plan for osteosynthesis with direct anterior screw fixation was made.

1. Operation

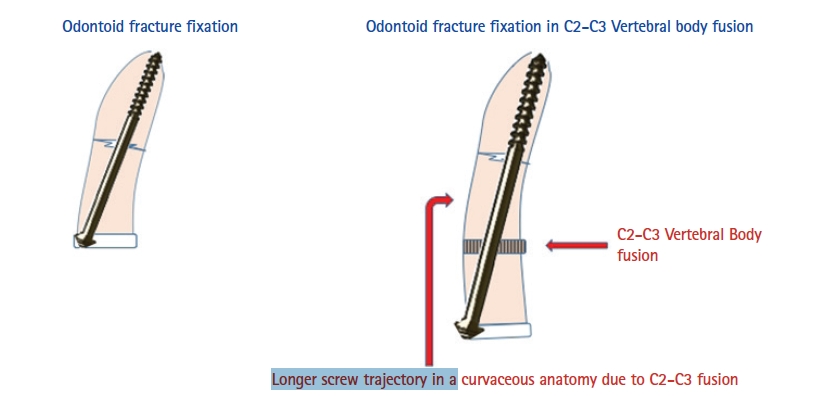

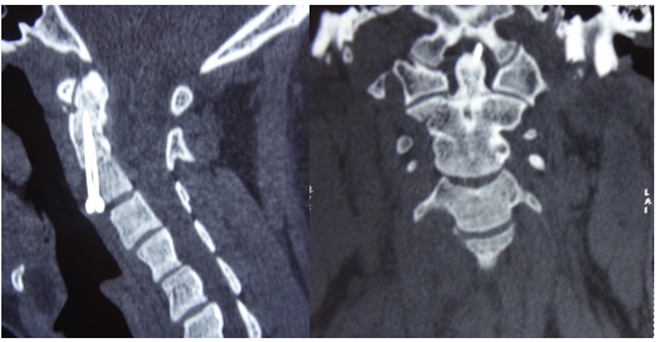

A horizontal 2 cm incision over the skin crease was taken at the C5–C6 level. Anterior neck dissection was carried out between appropriate tissue planes. The C3–C4 interspace was localized using bi-planar fluoroscopy. A pilot hole was driven through the C3–C4 intervertebral space starting exactly in the midline at the inferior aspect of the C3 vertebral body. Reduction manoeuvre was performed under anaesthesia with digital manipulation of the proximal fragment intra-orally under fluoroscopy guidance. The guide wire was driven using a power-drill through the proximal and distal fragments. The direction and the trajectory gets tricky in situations with C2–C3 fusion because the bony anatomy is rendered more curvaceous (Figure 3). A core drill was used followed by a tap to delineate the screw trajectory. A 55 mm length partially threaded 3.5 mm diameter cancellous screw was driven through the fracture, such that a strong purchase was achieved in the distal cortex to accomplish compression at the fracture site. Position of the screw was confirmed fluoroscopically. The wound was closed in layers following haemostasis and cosmetic sub-cuticular sutures were applied.

DISCUSSION

Direct anterior screw fixation in odontoid type-II fractures is an established treatment option [3]. This surgery not only provides excellent osteosynthesis and stability but also restores the rotatory movement at the C1–C2 joint in up to 83% of the patients, when compared to the other options of C1–C2 fusion [4]. Other advantages include avoidance of the long posterior incision, immediate patient mobilization and short hospital stay [5-7]. The focal point of the technique is identifying the C2–C3 intervertebral space and using the inferior aspect of C2 vertebra for screw placement. This served as a stumbling block in the described patient who had a congenitally fused C2–C3. The prevalence of a fused C2–C3 is between 0.5% to 6.5% [8,9]. The rarity of the condition is responsible for the limited literature on the same. This technique was historically contraindicated in patients with an inaccessible C2–C3 intervertebral space, necessitating a conservative approach or a posterior surgery [10]. This is only the second such case described in the literature [10]. Posterior surgery included either a trans-articular screw placement or a segmental lateral mass fixation and fusion [11]. The patient in this case report had a congenital C2–C3 fusion which meant absence of a normal motion segment at the C2–C3 level. A fusion at C1–C2 as a treatment option, although not wide of the mark, would sacrifice vital movement of flexion and rotation at an additional adjacent level resulting in a stiff neck in a young individual. The motion preservation property of the direct anterior screw surgery prompted the authors to conceptualize the described technique in the patient. In this technique the C3–C4 intervertebral space was identified and the central and inferior aspect of the C3 vertebral body was used as the screw entry point. A longer than usual cannulated cancellous lag screw measuring 55 mm was used for the same in view of the longer trajectory. The authors emphasize the stocking of longer screws in the surgical armamentarium in such cases (generally, odontoid screws measure 35–45 mm in length) [12-14].

CONCLUSION

Direct anterior screw fixation is a feasible management option in patients with type II odontoid fractures in the background of a fused C2–C3. Use of a longer screw owing to the longer trajectory and the entry point at C3–C4 intervertebral space are the subtle modifications required to facilitate this procedure.