INTRODUCTION

Lumbar canal stenosis (LCS) is one of the most common degenerative spinal disorders affecting the elderly with an incidence of 1.7%–8% [1,2]. Out of these 60% is multilevel LCS [3]. More elderly are being diagnosed with LCS due to increased survival rates, advent of MRI and a demanding lifestyle. Failure of conservative treatment is an indication for surgical intervention which may range from decompression to decompression plus fusion. While laminectomy has been the gold standard procedure for LCS, the proponents of minimally invasive spine surgery have refined the technique with goals to minimize morbidity and promote early recovery. The advantages of minimally invasive spinal decompression are well established in literature [4-11]. While, the outcomes of tubular decompression for single level LCS are well recognised, the nuances and results of their application in multilevel stenosis have been rarely reported in literature. The aim of this study was to assess the surgical outcomes of cases with multilevel stenosis that were operated using a tubular retractor through a single incision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

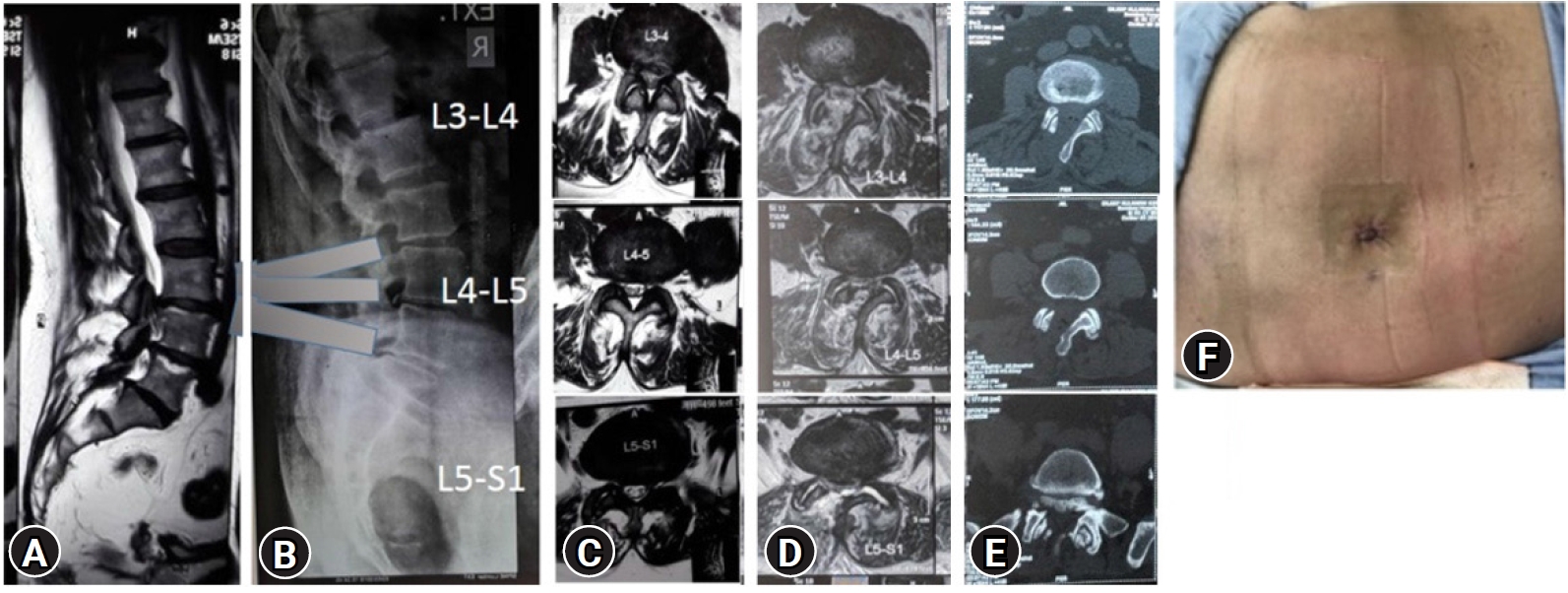

After approval of the institutional review board of Bombay Hospital and Medical Research Centre (approval no. BHIRB7989), a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients undergoing TD for neurogenic claudication from January 2007 to January 2018 was performed. 502 patients with neurogenic claudication operated using tubular retractors by a single surgeon were identified. The inclusion criteria for the surgery was disabling pain due to neurogenic claudication unresponsive to a conservative line of treatment and who had an adequate clinico-radiological correlation with two-three level spinal stenosis on the MRI.

1. Surgical Technique

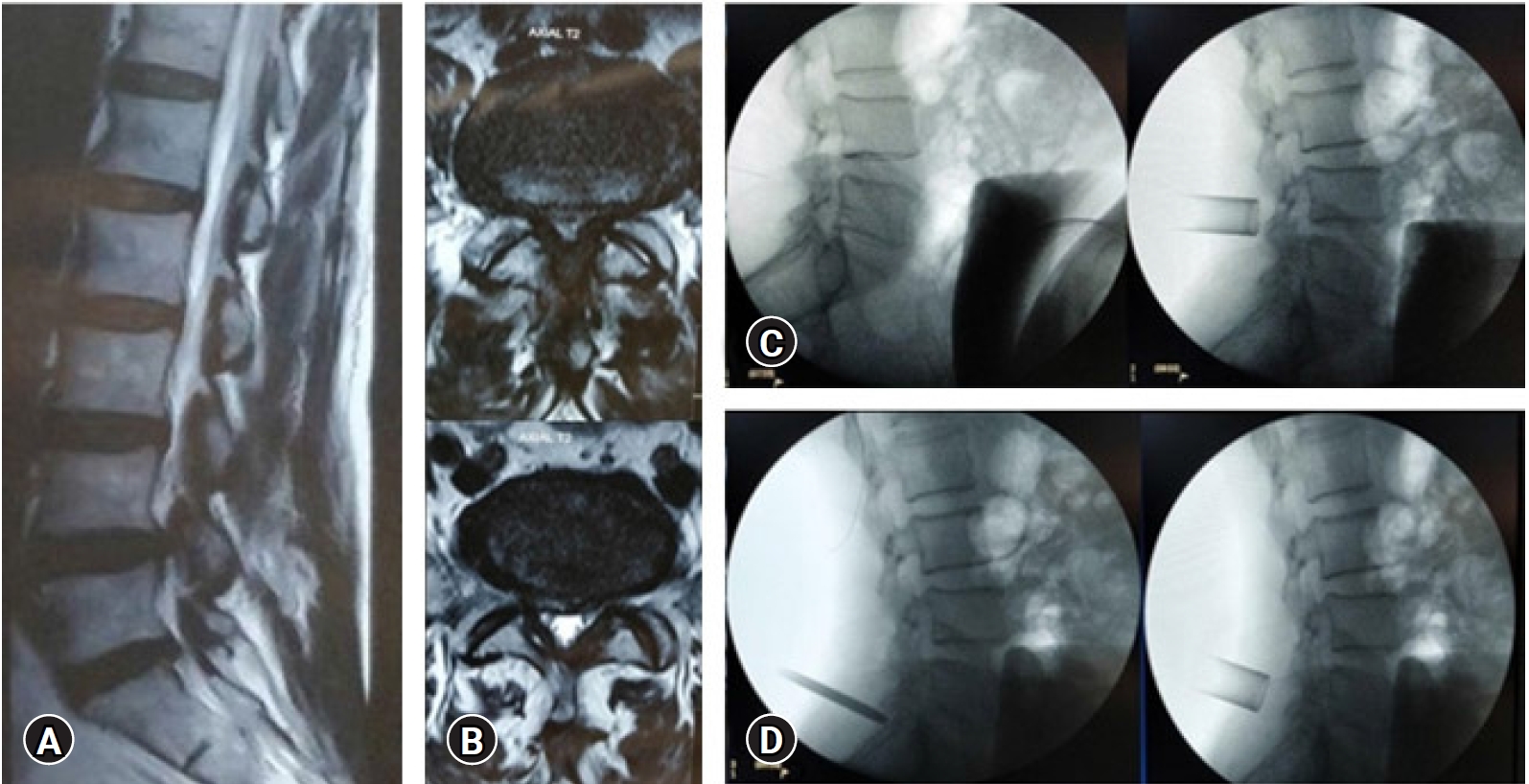

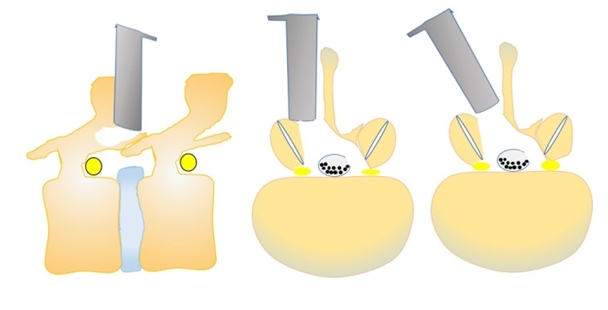

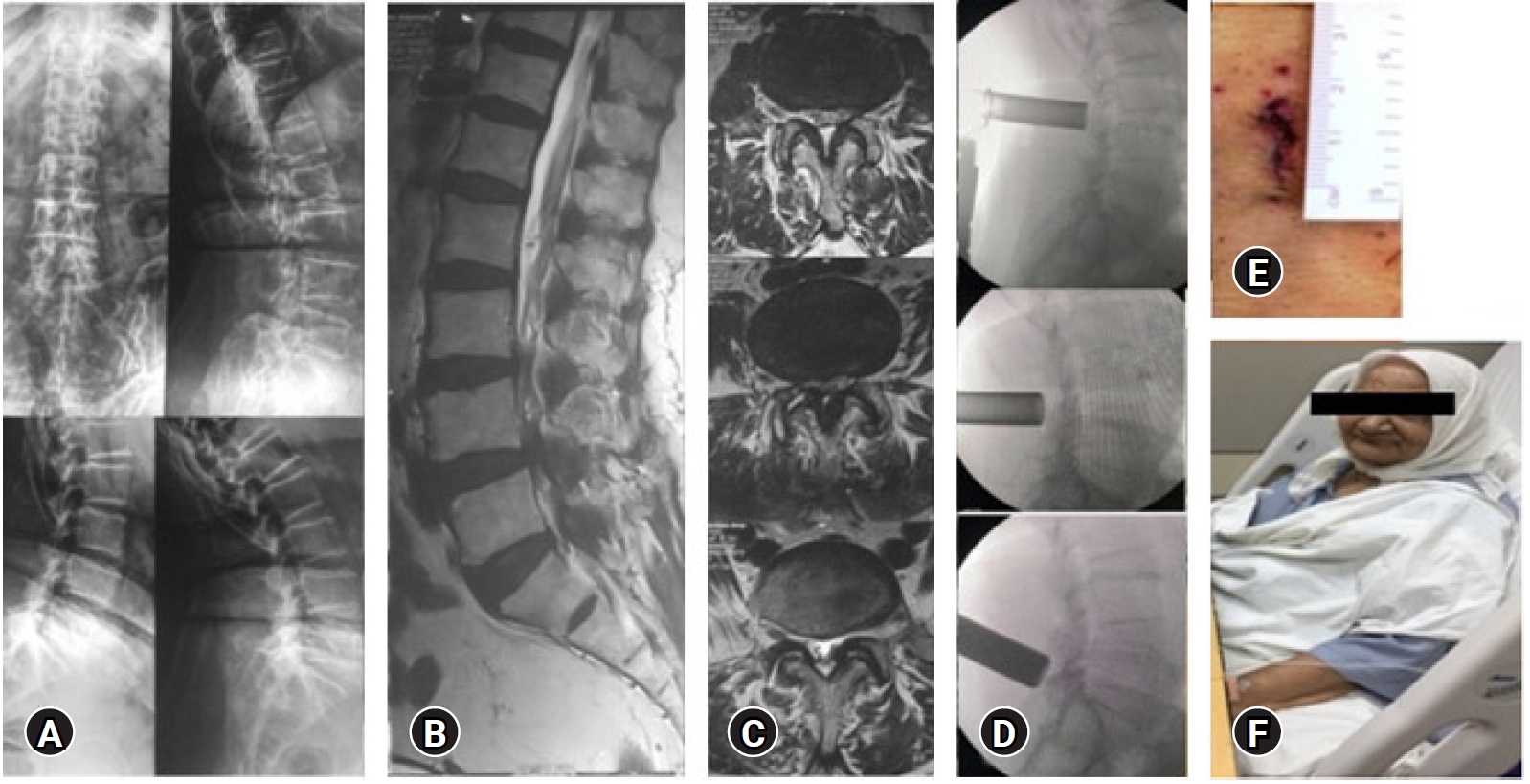

The patient was positioned on a radiolucent operating table on two well-padded horizontal bolsters and a silicone face support under general anaesthesia. The midline was marked with manual palpation of the spinous processes, in reference to which a para-median vertical line was drawn at a distance of 0.8–1 cm from the midline. An antero-posterior (AP) c-arm image to mark the midline may be necessary in extremely obese patients in whom the spinous processes were not palpable. A 20G spinal needle was then inserted through the para-median line such that the needle trajectory bisects the disc space of the involved level under c-arm control. The same spinal needle can be re-oriented in the trajectory/ies of the adjacent levels to verify the feasibility of decompression of those levels. This manoeuvre gives a sense of confidence to the operating surgeon about the feasibility of performing decompression of the adjacent levels through the same port. Once the spinal needle was docked on the inferior part of the superior lamina of the level to be decompressed first, the needle track was infiltrated with local anaesthetic (15 mL of normal saline and 5 mL 0.5% Bupivacaine) to provide pre-emptive analgesia. A vertical skin incision of 20 mm length centring over the entry point of the needle was scored along the paramedian line. The dissection was then carried deeper and the lumbar fascia incised. Tubular dilators (METRx System, Medtronic SofamorDanek, Memphis, TN) were inserted in the increasing order of diameters to dilate the muscular opening and a 18 mm diameter tube of appropriate length was docked over the inferior part of the superior lamina. C-arm was then used to verify the correct placement of the tube (Figure 1). It is important to create a sub-fascial plane initially at all the 2 or 3 levels that would require decompression by elevating the soft-tissues with the first dilator. This step has the advantage of re-assessing the feasibility of introducing and operating through a single port even before the surgery commences. The other advantage is that it will prevent the calamity of causing any kind of dural or neurological injury while re-introducing the dilators to execute decompression at the adjacent levels since the dilators will tend to march through the least resistant track of the operated index level. Once the tube position was ascertained, soft tissue was cleaned up and a high-speed burr (MidasRex, Medtronic SofamorDanek, Memphis, TN) and Kerrison punches were used to perform laminotomy of the superior lamina of the affected level. This was followed by an over the top decompression, that starts with drilling the base of the spinous process and the inner cortex of the contralateral lamina all the way to the lateral recess of the other side followed by step-wise excision of the ligamentum flavum (Figure 2). It is important to perform all the bony work before starting the flavectomy. Following flavectomy, the lateral recesses with traversing nerve roots on both sides were decompressed. This was followed by similar decompression at subsequent levels after angulating the dilators and the tubular retractors through the previously traced channels for the adjacent levels. The skin on the lumbar spine is mobile and can be slid downwards or upwards to aid in achieving a desired tube trajectory. The authors noticed that it was easier to re-dock the tube and achieve a good trajectory at the adjacent levels in obese patients with thick skin, subcutaneous tissue and para-spinal muscles (Figure 3, 4). This ‘posterior obesity’ necessitated the use of longer tubes and helped achieve a favourable tube trajectory. Skin was closed using 2-0 vicryl and 3-0 monocryl for subcutaneous and sub-cuticular layers respectively.

The authors timed the length of operation in minutes, from skin incision till the application of surgical dressing and calculated the blood loss in millilitres. The hospital stay was counted in days. All the patients completed a pre-operative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scale and ODI (Oswestry Disability Index) questionnaire and at post-operative day 1, 3 months, 6 months and 24 months and latest follow-up.

2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 23, IBM Inc.). The Univariate analysis included tabulating frequencies for ordinal and categorical variables and calculating the standard deviation, ranges and means for the continuous variables. The ODI and VAS scores between pre-operative and post-operative day 1, 3 months, 6 months, 24 months and the latest follow-up were compared. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 at 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

Of the 502 patients of lumbar canal stenosis operated for TD, 68 (13.54%) satisfied the inclusion criteria. Five patients were lost to follow-up and study was completed on 63 patients. All the patients agreed to take part in the study and to fill in the patient-based clinical outcome questionnaires. The mean duration of follow-up was 30.4 months (6–40 months). The mean age was 63.4 years (50–88) with a standard deviation of 18.6 years. There were 37 males (59%) and 26 females (41%). The mean BMI of the patients was 28 kg/m2 (23.6–38.4 kg/m2) (Table 1).

1. ODI and VAS Scores

The VAS improved from mean 3 (2–5) to 2 (1–4) and 7 (4–9) to 2 (1–5) for back and leg pain, respectively; while the ODI improved from a mean 44.6 (32–68) to 20.2 (16–42). The improvement on modified VAS and ODI was statistically significant (p<0.05) when a comparison was made between pre-op scores and most recent follow-up score (Table 2).

2. Complications

Two (3.17%) patients had dural tear with CSF leaks. Both the cases were diagnosed intra-operatively and the muscle and fascial layers as well as the skin were closed in a water-tight fashion. The mobilization protocol was similar to others without dural tears. One patient (1.6%) had persistent S1 dermatomal leg pain (index L3-4, L4-5 and L5-S1 decompression). He demonstrated radiographic evidence of persistent lateral recess stenosis at L5-S1 level and was re-operated with a tubular approach successfully. None of patients had any evidence of surgical site infections, medical complications or death.

DISCUSSION

Multilevel lumbar canal stenosis is not an uncommon situation. Conventional laminectomy necessitates a longer incision, a deeper dissection leaving behind a large dead-space, scarring of the paraspinal muscles and the possibility of spinal instability [12]. Tubular decompression has gained popularity over the last decade and has established itself in the management of single level LCS. The benefits in terms of cosmesis, minimal collateral damage of supporting bony and soft tissue structures, minimal dead-space, low rate of infection and early recovery make it a much more attractive option in the management of multi-level stenosis. The outcomes and technical nuances of performing tubular decompression for multilevel stenosis through a single incision are non-existent in literature. The current paper highlights the technical feasibility and positive clinical outcomes of tubular decompression performed in patients that suffer from multi-level LCS. The patient-based clinical outcomes like ODI and modified VAS showed a positive trend during the post-operative period of the procedure and were maintained at the last follow-up. The patients were immediately mobilized either on the day of surgery or the next day and discharged either on the first or second post-operative day. There was no requirement for a closed suction drain and the infection rate was zero with no instances of hematoma formation/soakage, etc. None of the patient needed a delayed stabilization procedure as a result of post-operative instability. This issue finds resonance in the cadaver study by Lu et al. [13] in 1999 which proved that multi-level laminotomies/fenestrations do not affect the lumbar spine stability in lateral bending and axial rotation. They concluded that as compared to laminectomy, multi-level laminotomies are effective in preserving stability of the lumbar spine. After an extensive literature search, we could only find one published manuscript in relevance to our study. The recent study by Lim et al. [14] involving 450 patients with multilevel stenosis operated by percutaneous lumbar decompression. They achieved good results with the use of an endoscopic technique.

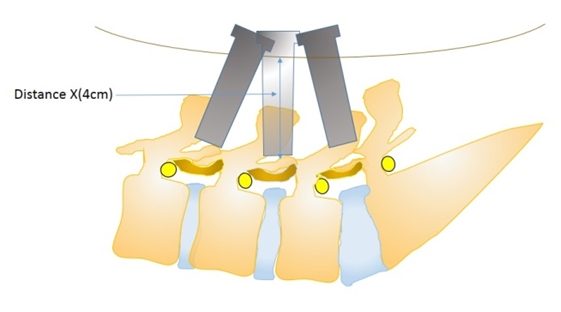

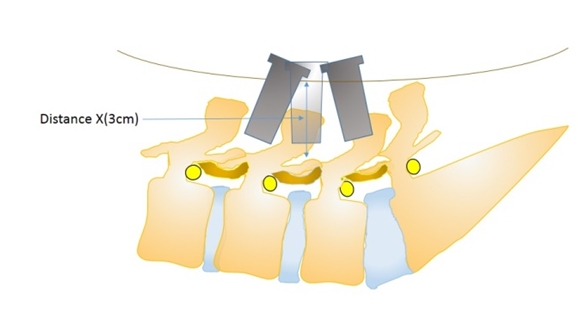

1. Posterior Obesity

Obesity plays a significant factor in these cases. Obese patients benefit the most from this single-incision-multi-level minimal access decompression. On one hand obese patients tend to have problems like difficult exposure, retraction of tissues, increased dead-space leading to hematoma formation, need for a drain, infection, poor healing etc. in reference to conventional laminectomy. These issues can lead to significant morbidity and poor recovery. On the other hand, this technique of single-incision-multi-level minimal access decompression appears tailor-made for obese patients. The authors realised that tubular retractors are held better by the tamponade effect of surrounding soft-tissues in obese patients, compared to thin patients. Again, the need for the use of longer tubes (60 mm/70 mm) in obese patients (increased distance between entry point on the skin surface and the docking point over the lamina) that act as lever in achieving the desired tube trajectory (Figure 5–7). Additionally, an increased skin elasticity in the lumbar area helps in decompressing 2–3 levels through the same skin incision.

All five three-level stenosis cases (L3-L4, L4-L5, L5-S1) operated in the study were obese (BMI>32) and their vertebral column was deep. All of these cases had a thick back. Hence, we coined the term “Posterior Obesity” in these cases with thick para-spinal musculature and subcutaneous fat.

CONCLUSION

The outcomes support the feasibility of performing TD through a single incision in cases of multilevel lumbar canal stenosis. This is probably the first paper in literature elaborating on the technical aspects and clinical results of performing a two-level or three-level TD through a single incision. Posterior obesity marked by increased distance between the skin surface and the lamina as shown in this study helps in getting a precise tube trajectory for multi-level decompression through the same skin incision.