INTRODUCTION

The concomitant occurrence of scoliosis and spondylolisthesis is retrieving in 15-48% of cases [14]. This association is etiologically classifiable in three groups: type-1: unrelated thoracic idiopathic scoliosis and lumbar spondylolisthesis; type-2: antalgic low-grade spasm scoliosis secondary to spondylolisthesis; type-3: lumbar scoliosis secondary to an asymmetric olisthetic defect [2].

Type-1 is reported in 6.2% of patients with idiopathic scoliosis [5]. The combined treatment represents a challenge with Lenke-1C curves: the two arthrodesis areas must achieve corrections while preserving mobility as much as possible.

CASE REPORT

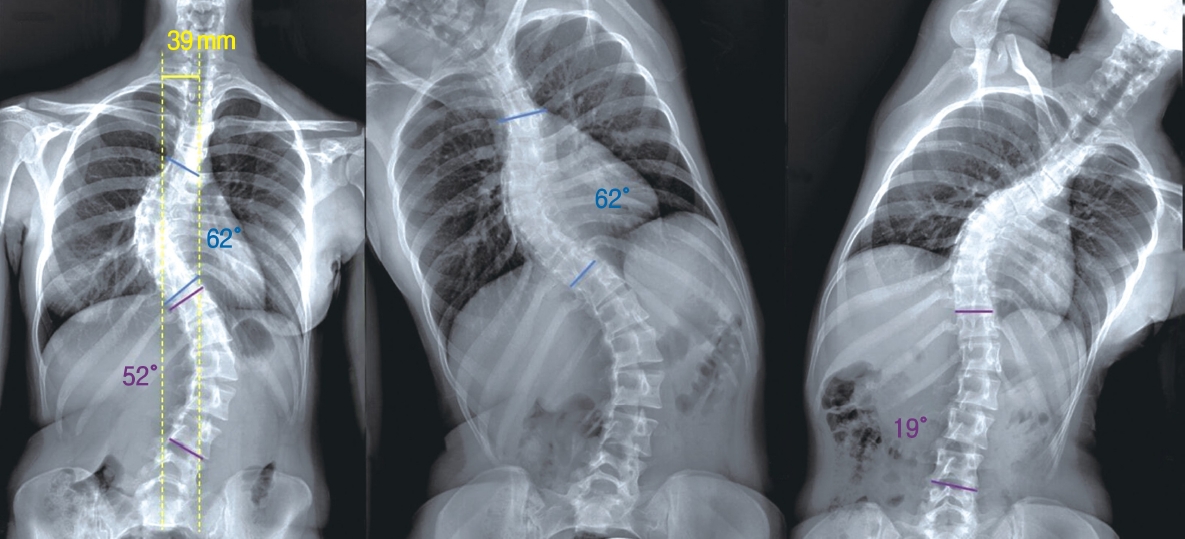

A 20-year-old girl presented low-back pain with bilateral L5 radicular pain, unresponsive to conservative therapies. X-ray showed a Meyerding grade-2 symptomatic high-dysplastic L5-S1 isthmic spondylolisthesis (Figure 1), with concomitant Lenke-1C scoliosis. Cobb angle of the main thoracic (MT) curve was 62°. The non-structural lumbar (L) curve was 52°, resulting highly flexible (19° at side-bending X-ray). Standing X-ray showed coronal imbalance: C7 plumb-line (C7PL)/central sacral vertical line (CSVL) distance was 39 mm (Figure 2). Previous follow-up X-rays had confirmed that both scoliosis and spondylolisthesis were progressive during the conservative treatment with TLSO Brace (Thoracic Lumbar Sacral Orthosis).

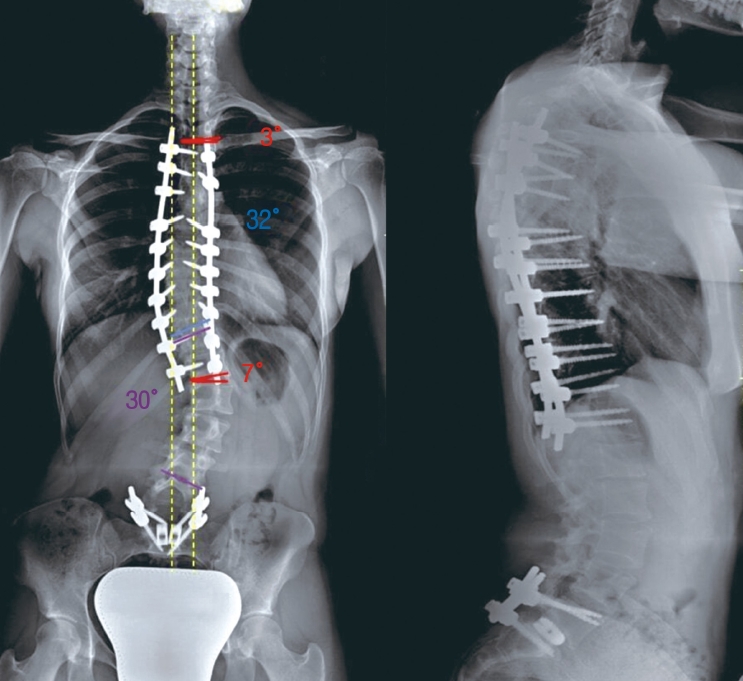

We performed one-stage correction of both deformities: T3-T12 selective thoracic spine fusion (STF) associated to reduction and fusion of the slipped vertebra.

The first incision was from T3 to T12. To increase spinal flexibility three apical Ponte osteotomies were performed. High-density uniplanar pedicle screws were placed with straight-forward Funnel technique. A translation maneuver was applied adopting two asymmetric 5.5 mm cobalt-chrome rods. Rods were overshaped on the desired kyphosis apex (T6) to obtain a lifting effect restoring kyphosis. At the scoliosis apex, the rod on the concave side was over-shaped and the rod on the convex side was under-shaped, to obtain a rotational effect achieving deformity correction. Direct vertebral rotation was applied to complete correction [4].

Through a second incision, two polyaxial reduction screws were placed in the L5 pedicles and two polyaxial screws in S1. The posterior mobile arch was removed in block; discectomy was performed, and the slippage was reduced. Two titanium cages of appropriate size were placed.

1-month post-operative X-ray showed a reduction of MT-curve to 32° and L-curve to 24°. The coronal imbalance was reduced to 13 mm. A satisfactory sagittal alignment and olisthesis reduction were achieved (Figure 3). At 24-months follow-up, X-ray showed an increase of L-curve to 30°. C7PL/CSVL distance was 24 mm(Figure 4). No further loss of correction appeared at 36-months follow-up.

DISCUSSION

When Lenke classification was developed [11], the intent of the Authors not only was to describe AIS curve types, but also to help the surgeons deciding specific vertebral levels to be included in spinal arthrodesis. According to the Authors, the major curve has the largest Cobb angle and should always be included in the fusion. Whether or not the minor curves should be fused depends on their flexibility and how the deformity affects the sagittal plane [11]: if a minor curve corrects to <25° on coronal side-bending films and if, in addition, the kyphosis between T2-T5 and T10-L2 is <20°, the curve is regarded as being non-structural and does not have to be included in the fusion because spontaneous coronal correction after selective fusion of the major curve is expected [9]. Therefore, STF can be performed when both the thoracic and the TL/L curves deviate from the midline, but only the major curve is fused, leaving the minor curve(s) unfused and mobile [3]. This procedure has been proven successful in Lenke-1 and Lenke-2 curves [6,9] and in Lenke-3 curves when specific criteria are met (MT:TL/L Cobb, AVT-MT: AVTTL/L and AVR-MT:AVR-TL/L >1.2) [3]. However, Lenke-1C curves treated with STF have a higher risk of post-operative coronal decompensation than A/B [3,8,10]. Kwan et al., about STF outcome, stated the risks of coronal decompensation of 20.5%, lumbar decompensation of 9.1%, adding-on phenomenon of 25.0% [10].

Coronal imbalance can lead to aesthetic concerns, rarely to the need to extend the fusion [10,12,15]. While the main causes of immediate post-operative decompensation (IPCD) following STF have been widely investigated (pre-operative coronal decompensation, excessive MT-curve correction, inappropriate selection of LIV), less is known about spontaneous correction of L-curves [7,13,16]. It may be attributed to postural reflexes, potentially existing in the relatively flexible non-structural curves. Ishikawa et al. reported STF with LIV proximal to SV leads less frequently to IPCD, but it results in lower correction of the non-instrumented L-curve [7]. Conversely, not-selective fusion with LIV distal to SV would result more frequently in IPCD, but with a higher trend to progressive L-curve recompensation. Nevertheless, patients with coronal decompensation at final follow-up all had IPCD, and none of the post-operatively compensated patients resulted decompensated at final follow-up.

In the presented case, considering the curve type, the age of the patient, the L5-S1 arthrodesis, and wanting to preserve as much movement as possible, the Authors chose to treat the Lenke-1C scoliosis with STF. In fact, despite the higher risk of coronal decompensation when compared to Lenke-1A and B curves, STF has been demonstrated as an effective treatment for the so-called "false double major" curve (Lenke-1C/King II) [1]. Moreover, STF maintains the option to extend the fusion to the lumbar spine when the non-instrumented curve is found to be progressing. Hypothetically, the choice of LIV was intended to balance the risk of IPCD without sacrificing the progressive coronal compensation capacity of the L-curve. However, postoperative X-ray showed a certain degree of IPCD (despite an improvement from pre-operative condition), but coronal misalignment progressively increased at the 3-, 6- and 12-months follow-up, remaining stable up to the final 3-years follow-up.

The indication to perform a combined one-staged surgery in the patient was driven by the evidence that both pathological conditions were already progressing and worsening, as well as clearly symptomatic. We considered that both interventions had to be performed, so we avoided a two-staged surgery (first the scoliosis correction and then the spondylolisthesis, or vice versa) in order not to risk further worsening of the pathology not surgically treated, caused by the biomechanical changes secondary to the first intervention. Obviously also the possibility to avoid a second general anaesthesia and a second rehabilitation program contributed to our decision.

This case supports our opinion that distal lumbar arthrodesis, by tightening the L-curve reducing its compensation potential, may represent a risk-cofactor for the occurrence of lumbar adding-on following STF. This should be considered in planning the arthrodesis area in similar cases. However, we believe that STF is justified as worsening the lumbar curve does not balance the possibility of preserving the motility of the lumbar tract, also because the need for revision is an uncommon event for these issues.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, although the evidence cautiously suggests STF to treat also Lenke-1C scoliosis, the risk of worsening coronal decompensation and adding-on exists and it is possibly increased by association with spondylolisthesis. In Authors' opinion, this report adds useful elements in the choice of treatment in a challenging scenario such as the case presented.