INTRODUCTION

Tethering of the spinal cord can occur in a number of settings, including post-traumatic, post-surgical, herniation through dural defects or in the presence of congenital anomalies [4,16].

Spinal lipomas are thought to be a result of failed primary neurulation [11]. They are some of the most common pathologies encountered in pediatric neurosurgery, however, intradural lipomas that are not associated with bony dysraphism (other than simple filar lipomas) are rare, representing less than 1% of all intra dural tumors [1,3,5-7]. Of this group, lipomas located in the thoracic spine are exceedingly rare. Intramedullary lipomas have a bimodal distribution of presentation, first during infancy or early childhood and secondarily in the third to fourth decades of life [15].

Lipomas typically cause neurologic deficit as a result of their mass effect, behaving similarly to spinal cord tumors [9]. Additionally, spinal lipomas cause neurologic deficit by tethering, in which symptoms arise due to traction longitudinally on the spinal cord [16]. There is some research to suggest the pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome is secondary to reduced blood flow, impaired oxidative metabolism, and hypoxia associated with elasticity of the spinal cord [2].

The case described here is the first report to our knowledge, to detail an unusual occurrence of a symptomatic tethered thoracic spinal cord due to an intra- and extra-medullary lipoma that was difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Subsequently, the case was managed successfully with minimally invasive surgery. A literature review was also conducted.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

1. Ethical Approval

With Institutional Review Board approval with waiver of consent, a chart review was conducted on this novel case.

2. Case Report

The patient is a 26-year-old male with a history of chronic low back pain that was first evaluated in a neurology outpatient clinic. There was a three-and-a-half-week history of insidious onset bilateral lower extremity ascending numbness. Sensory deficit was bilaterally symmetric, constant, and did not change with activity or position. He had sustained an 80 foot fall down a mountain while serving in the military approximately 5 years prior, but denied recent trauma or falls. He subsequently reported involvement of his bilateral upper extremities with numbness in his fingers. There was no significant bowel or bladder incontinence, nor saddle anesthesia. There was no family history of neuromuscular disorders or multiple sclerosis.

His neurological examination was significant for complete loss of sensation to light touch and reduced vibration sense from the level of waist down bilaterally. He had intact deep pressure sensation and proprioception. His strength was full in all muscle groups. His patellar reflexes were 3+ bilaterally without clonus, Hoffman’s sign, nor Babinski’s sign. Diagnostic electromyography (EMG) and a nerve conduction study (NCS) showed absent sural and superficial peroneal nerve sensory responses suggestive of peripheral polyneuropathy that was length-dependent. The upper limb sensory responses were preserved, with mild bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. Of note, he had had an EMG of the bilateral lower extremities 2 years prior, which was normal. Extensive blood work was unrevealing. Cervical and lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were unremarkable. Chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography (CT) revealed no obvious signs of malignancy. There was evidence of a thickened terminal ileum and rectum for which the patient had undergone an endoscopy with negative biopsies.

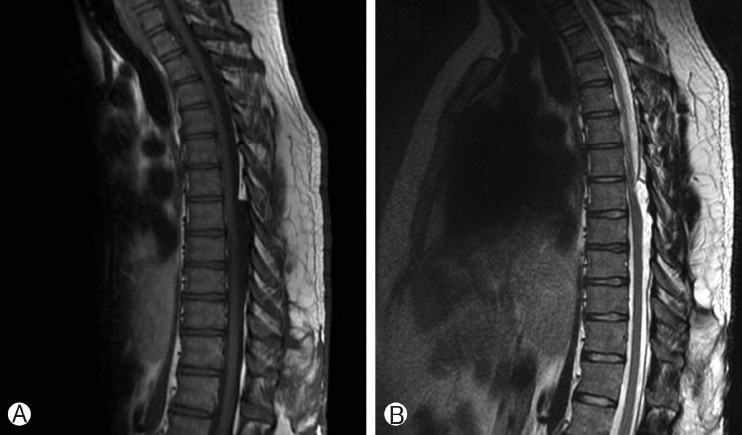

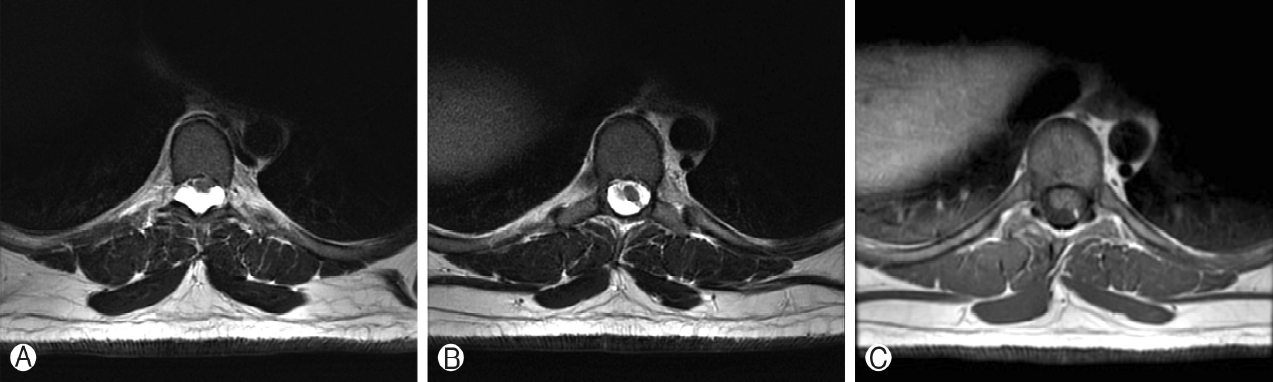

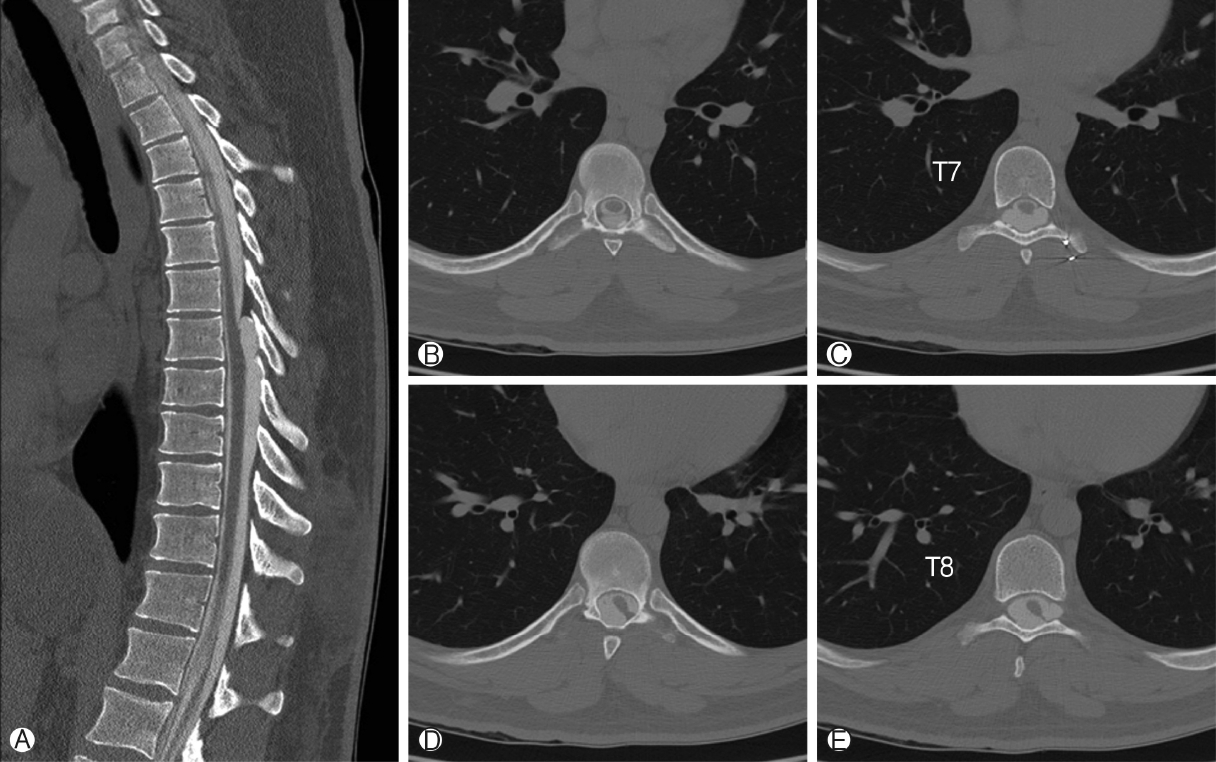

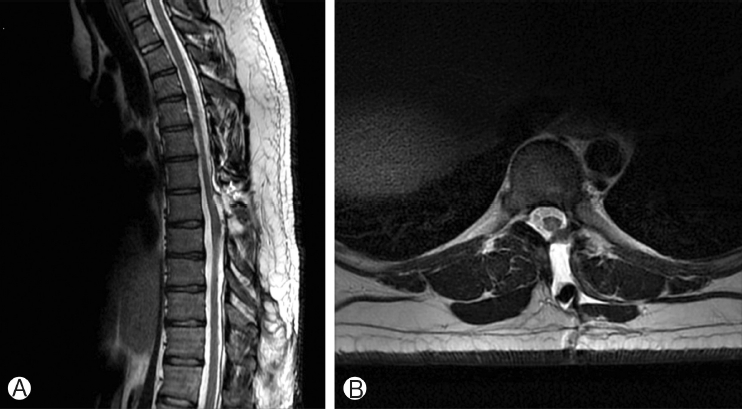

Thoracic spine MRI showed a T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense, non-enhancing lesion in the intradural, extramedullary space of the dorsal spinal canal at T6-T9, measuring 9 mm in anterior-posterior diameter (Figure 1A, B). This lesion had resulted in ventral displacement of the spinal cord, and appeared to be associated with absence of the posterior epidural fat (Figure 2A). The lesion did not restrict diffusion. At the superior margin of the lesion, there was a thin T2-hypointense, T1-hyperintense band of tissue thought to represent a fibrous adhesion, which extended through the dorsal lesion and appeared to tether the spinal cord to the left dorsal-lateral aspect of the spinal canal (Figure 2B, C). Subsequent CT myelogram demonstrated contiguity of the dorsal intraspinal lesion inferiorly with the thecal sac, multilevel lobular dorsal expansion of the thecal sac, transient flow limitation at the superior margin in the region of the fibrous tissue band, and tethering of the thoracic spinal cord to the left dorsal-lateral surface of the thecal sac (Figures 3A-E). Ultimately, after review by multiple neuroradiologists, these findings were thought to represent a form of dural ectasia extending into the epidural fat, resulting from altered cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow dynamics created by the fibrous band. The patient was indicated for surgical exploration and spinal cord detethering due to progressive neurological deficits.

3. Surgical Technique

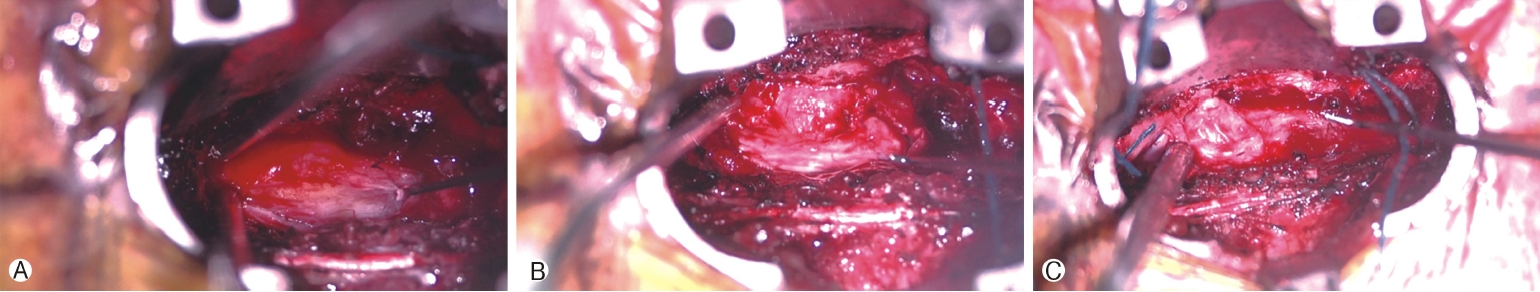

Surgical exploration was carried out by a minimally invasive, unilateral, trans-muscular, paraspinal approach using the Quadrant retractor (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) exposing spine levels T6 to T8. The left hemilaminae and ipsilateral medial facets of T6 to T8 and the base of the spinous processes were removed. The ligamentum flavum was dissected and removed. Underneath, an abnormally thin and unusual appearing, but apparently intact, dura was encountered. Nevertheless, scant amounts of CSF were observed entering the field. Rostrally and caudally the abnormal appearing dura had a bluish and ballotable appearance. However, in the central area of the decompression, dura had a yellowish, ovoid appearance, which to palpation was solid. A small opening in what was suspected to be dura just medial to this firm, yellowish area was made and the subarachnoid space entered, where brisk CSF drainage was encountered and the right lateral aspect of the spinal cord was visualized. The spinal cord was observed to be tethered to a yellowish mass in the dura by a dorsal band of adipose tissue (Figure 4A). While similar to a narrow, paramedian dorsal lipomyelomeningocele, the fatty mass did not extend through the dura nor was there any bifid dorsal bony structure appreciated. A small biopsy of this area was sent for frozen section and subsequent pathology analysis.

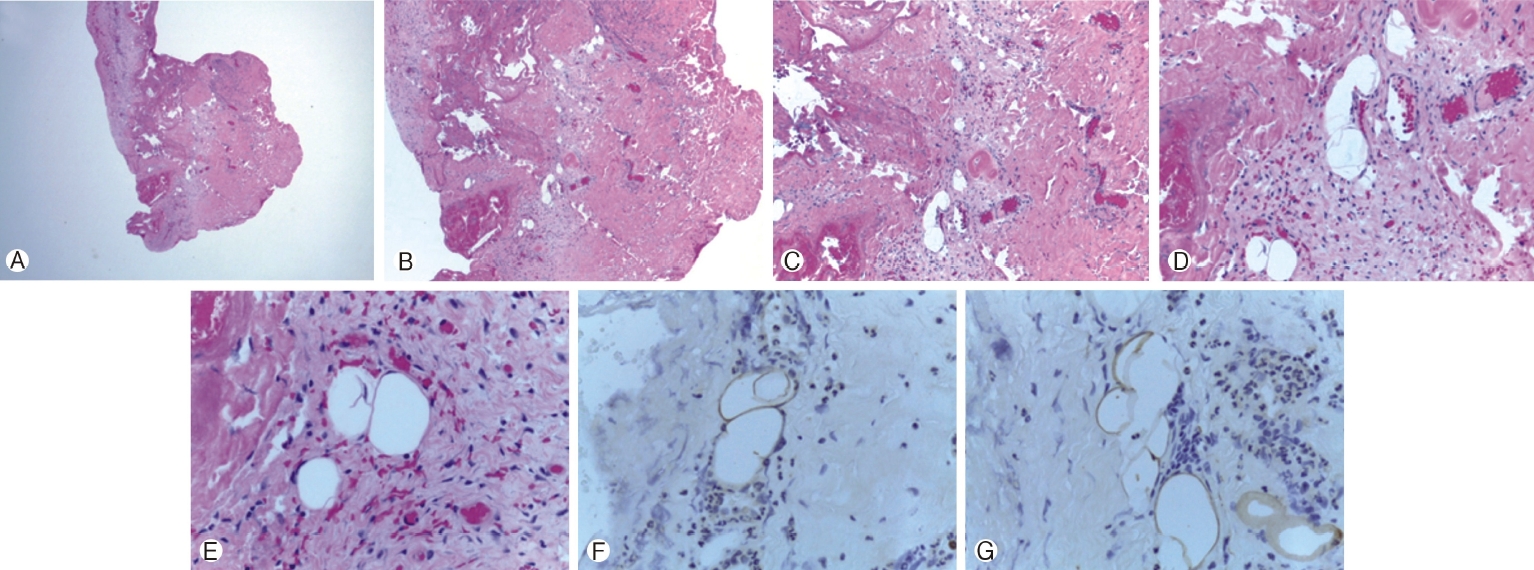

A microsurgical technique to open the dura circumferentially around the attachment of the fatty mass (Figure 4B), was used; very carefully opening the arachnoid, and separating the mass and its overlying dura from the surrounding, intact dura, but leaving an island of abnormal dura on the dorsal surface of the mass. Nerve roots on the patient's left side were identified and preserved. After a period of careful microdissection, the mass was entirely free of the dura with a circumferential dissection around it. The mass was observed to be mushroom shaped (Figure 4C), and resection of the flanges of this mushroom was undertaken while leaving the central area, which arose directly from the dorsal spinal cord intact. Neuro-monitoring was not available to ensure that the dorsal columns of the spinal cord were not entered. The resected tissue was submitted to pathology for analysis (Figures 5A-G).

At closure, a dural substitute (Biodesign, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) was used. It was trimmed to a shape that would fit intradurally inside the dural defect and tucked underneath the dural edges so that CSF pressure would aid in closing the defect. The tenuous dura was not deemed appropriate for direct suture repair. This onlay closure was sealed with fibrin glue. The bony defect created by the approach was then closed with 5 mL of HydroSet hydroxyapatite bone cement (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) over the dural repair.

4. Post-Operative Management

The patient woke from anesthesia with significant improvement in his bilateral lower extremity sensation. The patient was managed postoperatively in three degrees of Trendelenburg for 48 hours. He was allowed to sit up, and he was discharged on postoperative day three. He was subsequently seen in clinic for a 2-week follow up visit at which time his bilateral lower extremity numbness had resolved completely. He also reported that his legs felt “hyper-sensitive.” At a 3-month postoperative follow up, he reported the numbness in his legs, gait difficulty, and hypersensitivity had resolved. He reported no headaches.

DISCUSSION

We report a case of a successful uniquely minimally invasive surgical treatment approach of a rare spine lipoma. This intradural, mixed intra- and extra-medullary mass presented here proved difficult to characterize by imaging. Despite the lipomatous component, it did not display prominent fat-signal on T2-weighted imaging. MRI findings initially suggested an arachnoid cyst. The fibrous adhesions and contiguity of the lesion with the thecal sac on myelography suggested the lesion more closely resembled dural ectasia. The final pathologic and intraoperative findings of a true spinal cord lipoma with tethering, lacking the more extensive dysraphic features of a lipomyelomeningocele, demonstrate a rare presentation of an even more rare entity.

There is a growing belief among surgeons that aggressive total resection of intradural lipomas is associated with poor out come and not required for neurologic improvements [5]. Though controversial, there is some evidence to suggest there is a high rate of recurrence, roughly 50% with partial resection at 2-10 years postoperativley, though many of these studies analyzed outcomes in patients with lumbosacral lipomyelomeningoceles, which may have a different natural history than presented in this rare case report [12,13].

One of the major challenges to surgical resection of spinal lipomas is distinguishing normal spinal cord tissue from lipoma. The minimally invasive approach to spine surgery as undertaken through tubular retractors was highly favorable in this case. This approach allowed for performance of a three level hemilaminectomy to span in the entire area of pathology in the rostro-caudal plane. Visualization of the dura was possible, which was unusually thin, including the raised yellowish-ovoid area that delineated the underlying attachment of the intradural lipoma which identified an appropriate biopsy site. Using a microsurgical technique, separation of the lipoma’s dural attachment circumferentially from surrounding normal thoracic spinal dura, thereby untethering the spinal cord, and subsequently relieving the patient’s sensory deficits was possible. Others have reported minimally invasive approaches for intradural lesions, but not previously for congenital thoracic spinal lipomas, to our knowledge [10].

Given that the thoracic lipoma attached to the inside surface of the abnormal dorsal thoracic dura, which was resected, repair of the resulting large complex opening in a watertight fashion was not possible. Alternatively, a dural substitute was inset to fit the dural defect and sealed with fibrin glue. Given the lack of a water tight dural closure, the minimally invasive tubular approach, which minimizes disruption of soft tissue and muscle, was highly important to ensure minimal risk of CSF leak compared to a traditional open approach. In this patient, while there was an expected post-operative pseudomeningocele, there was no CSF leak or infection. The literature supports this approach and its associated benefits, including reduced rates of surgical site infection and symptomatic CSF leak, along with shorter post-operative hospitalization time [14].

Although the tenuous nature of the dura did not allow dural suture closure in this case, suturing of the dura is quite feasible with tubular access surgery using bayoneted instruments and single throw sutures or clips. Open access would have allowed a laminoplasty approach, but otherwise would have major disadvantages, including more postoperative pain, more difficulty with prevention of CSF leakage, higher risk of wound infection, and more blood loss [8]. We believe the potential associated complications of the open spinal approach would outweigh its overall benefits and therefore selected a minimally invasive tubular approach for this unique and rare pathology.

CONCLUSION

This case of a thoracic spinal cord lipoma not related to bony spinal dysraphism was challenging to identify on pre-operative imaging, and ultimately was treated uniquely with a minimally invasive tubular surgical approach. A rare unusual pattern of imaging findings associated with thoracic spinal lipoma are presented. Feasibility of surgical excision of such a spinal lipoma with untethering through a minimally invasive tubular approach is demonstrated and found to be effective.